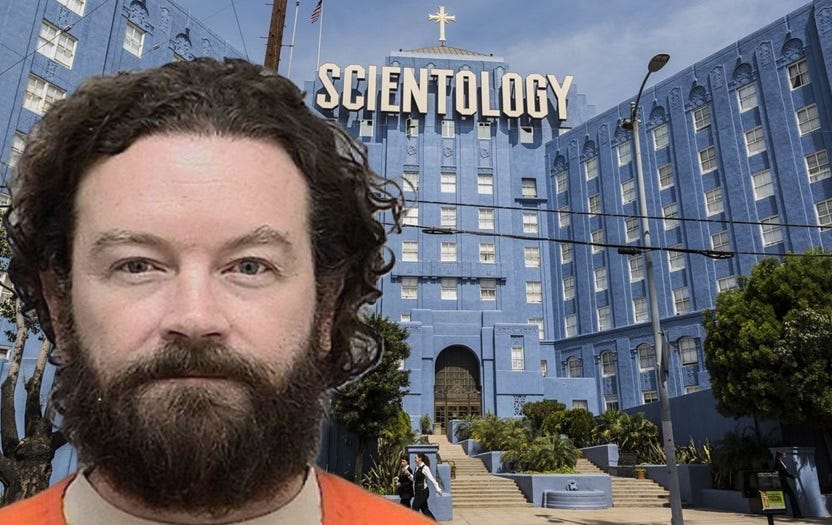

Here's Danny Masterson's entire appeal brief

Danny Masterson’s appellate attorneys turned in their appeal brief a couple of days early, and we knew you’d want to dig into it and give us your thoughts.

So here’s the whole enchilada. It’s too big to fit in an email, so please come to tonyortega.substack.com to see the whole thing.

And please keep in mind, as you see Danny’s attorney Cliff Gardner attack the credibility of these victims, a jury saw these women testify in person and believed them. We think that will go a long way with the appeals court.

UPDATE: The text of the brief now reflects the shorter, 35,000-word brief that the appellate court accepted.

INTRODUCTION

In 2023, appellant Daniel Masterson was convicted of forcible rape involving complaining witnesses [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] based on incidents occurring in 2003. The defense in this case was simple: appellant knew both women socially and the sex was consensual. There was no physical evidence supporting the state’s theory, there were no admissions, there were no inculpatory pretext calls. In the absence of such independent corroborating evidence, [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] were the pivotal witnesses for the state — their credibility would be critical to the state’s case.

After an initial investigation in 2004 as to [Jane Doe 1]’s claims, the District Attorney declined to prosecute. In June of 2020, nearly 16 years later, the District Attorney elected to go forward with charges involving three complaining witnesses — [Jane Does 1, 2, and 3]. The case was tried twice. The first jury deliberated six days, before hanging 10-2 for acquittal as to [Jane Doe 1], 8-4 for acquittal as to [Jane Doe 2] and 7-5 for acquittal as to [Jane Doe 3]. The second jury deliberated an additional eight days before once again hanging on the charge as to [Jane Doe 3] (which was later dismissed) but convicting as to [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2]. Whatever else may be said about the state’s case, it is clear that at both trials, jurors had significant reservations.

Here is why. As discussed more fully below, jurors at both trials learned that the testimony of both [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] changed dramatically over the years. To be sure, under the extremely deferential rules of appellate review, the testimony eventually offered at the two trials by both [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] was sufficient to support a conviction for forcible rape. But as shown by the protracted jury deliberations at both trials, the evolution of that testimony reflected a substantially changing narrative over time. The many changes over time — involving both sharply changing recollections as to some facts and the wholesale addition of new facts never before mentioned — consistently pointed in one direction: to a newly minted claim that force was used.

One explanation for these changes — offered by the prosecution — was that this is just how human memory works; sometimes witnesses do not disclose all the important facts at the first, second or third telling of their story but as they remember more or are asked different questions they disclose new and different information. (33-RT-3288.)

But there was another explanation that was grounded in the timehonored motive of financial self-interest. This motive involved both the civil and criminal statutes of limitation. On the civil side, the statute of limitations to file a lawsuit against appellant seeking damages for rape had long since expired by the time of trial. Under state law, however, if jurors convicted appellant of rape in a criminal prosecution, the civil statute of limitations would be revived and both [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] would have one year to seek monetary damages for rape.

But this one-year window of opportunity to file for civil damages would open only if appellant was convicted of forcible rape involving multiple victims. This is because the charged offenses occurred in 2003. Typically, the criminal statute of limitations for rape is ten years. But here, the prosecution offered an interpretation of the law which could avoid this potential bar. Under the prosecution’s theory, so long as appellant was convicted of forcible rape of multiple victims within the meaning of Penal Code § 667.61(e)(4) — as opposed to any other form of rape (e.g. rape by intoxication) — there was no statute of limitations bar and the criminal prosecution could go forward. And if the criminal prosecution went forward, and the jury convicted of at least two counts of forcible rape, then [Jane Doe 2] and [Jane Doe 1] would be able to sue for damages.

As explained in the Statement of Facts below, the record shows both [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] were well aware of the statute of limitations issues. [Jane Doe 1]’s own text messages showed that she had been made aware that unless the specific requirements of § 667.61 were met “the case can’t go forward.” As for [Jane Doe 2], in a tape recorded conversation, the prosecutor directly told her there were “statute of limitations issues,” the resolution of which depended directly on “certain acts that were done, and how they were done . . . .” Under the defense theory, the need to bypass the criminal statute of limitations, to allow a civil lawsuit for damages to proceed, explained the many changes in the recollections of both [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] which eventually supported claims of forcible rape.

These changes in recollection were stark indeed. As to [Jane Doe 1], the underlying incident occurred in April of 2003. By way of example only, three months after the April 2003 incident [Jane Doe 1] described the sexual encounter with appellant as follows to her friend P.D.:

[It was] the best sex [I] had ever had. . . . [because of] [t]he positions he had me in . . . [and] [t]he speed.

(8-CT-2316.) [Footnote 1. Because of the high profile nature of this case, and to protect the privacy of certain witnesses, appellant will refer to certain witnesses by initials only.] But 14 months later — in June of 2004 — [Jane Doe 1] reported to police that this same encounter was actually rape.

In her June 2004 police interview, [Jane Doe 1] admitted she and appellant had had consensual sex on an earlier occasion — in September 2002. Her friend J.W. told police that only hours before the April 2003 charged incident, [Jane Doe 1] told her how much she had enjoyed the September 2002 sex with appellant. (8-CT-2315.) But by the time of trial, this changed too: [Jane Doe 1] now told jurors the September incident was also forcible rape. And although [Jane Doe 1] recounted the April 2003 incident in two separate police interviews in 2004, it was not until 2017 — a full 13 years later — that [Jane Doe 1] claimed for the first time that appellant displayed a gun during the incident.

[Jane Doe 2]’s recollection also changed sharply over time. Like [Jane Doe 1], [Jane Doe 2] also knew appellant socially. At appellant’s invitation, she came over to his home one evening in 2003, they had wine, they kissed, they showered together and they had intercourse.

Fourteen years later, [Jane Doe 2] reported to police that this was rape. In her initial report to police and her pre-trial statements, [Jane Doe 2] said that (1) because she was nervous, she drank vodka and one or two glasses of wine before coming to appellant’s house that evening, (2) she “wanted [appellant] to kiss her” and when he did she “was getting into it with him,” (3) they showered together, although she could not recall whether taking a shower together was her idea and (4) after sex, they spoke to each other for hours on the bed and the bedroom terrace, and she thought they were going to “start dating.” By the time of trial, however, [Jane Doe 2]’s recollection changed. Now (1) she only had one or two sips of alcohol before coming to appellant’s house, (2) when appellant was kissing her she was saying “no, no, no,” (3) appellant “ordered her” into the shower and (4) her mother’s “takeaway” after speaking with her was that [Jane Doe 2] felt like appellant treated her “like a piece of meat.” But even at trial, [Jane Doe 2] admitted that several days after they had sex — when appellant had not called her — she called and told him “I really like you. I thought you liked me. I thought you were going to call.”

As more fully discussed below, there are numerous reasons reversal is required in this case. By the time the prosecution brought charges against appellant — 17 years after the 2003 incidents and 16 years after the prosecution initially decided not to prosecute — several witnesses died and police had lost critical evidence. The trial court’s ruling that prosecution was nevertheless proper not only ignores the plain language of the relevant statute of limitation, the Law Revision Commission Comment to the legislation, the location of the statute at issue, and fundamental principles of statutory construction, but it leads to results which the Legislature could never have intended.

Moreover, in a series of rulings the court fundamentally skewed the jury’s ability to resolve the credibility issues at the heart of this case. First, ignoring a century of case law, the court erroneously excluded evidence that the complaining witnesses had a direct monetary interest in the outcome of the criminal trial and a strong financial incentive to characterize the long past sexual encounters as forcible rape. The prosecutors took full advantage of this ruling in closing argument, again and again ridiculing the defense theory that there was a financial motive to falsely claim rape in the criminal trial, pointing out that this was nothing but speculation and no evidence supported a financial motive theory.

There is more. Because the complaining witnesses admitted to communicating with each other for years prior to trial, the defense theory was that their testimony had been contaminated. The court permitted the prosecution to respond to this theory by introducing testimony from 18-year police veteran Detective Myape that in her opinion, the ongoing communications between the complaining witnesses did not in fact contaminate their testimony. The court then barred defense counsel from eliciting neutral testimony from Myape that, in fact, she did not know one way or another whether the complaining witnesses were being truthful.

There is more. The court’s ruling as to Detective Myape was not the only ruling which undercut the defense theory that the complaining witnesses had shaped their testimony together. Because at the first trial these witnesses admitted communicating with each other for years prior to trial, and to more directly support the defense theory of contamination, the defense sought to subpoena these witnesses for digital and documentary evidence of their actual communications with each other. The court quashed these subpoenas, allowing the actual communications to remain secret to this day.

There is still more. To buttress its case against appellant at the first trial, the state presented Evidence Code § 1108 witness Tricia V. to testify that he raped her twice in 1996. But because defense counsel had time to prepare for Tricia V.’s testimony, on cross-examination she was confronted with a 2017 message she wrote to Chris Masterson, defendant’s brother, that she had heard the allegations and she “wanted to send you guys some support. Danny and you, too, were so protective of me, looked out for me and put [me] up when my BF cheated on me and I didn’t have a place to stay. Hope you are both doing well. XOX, Tricia.”

The prosecution did not call Tricia V. at the second trial. Instead, three weeks before the second trial was scheduled to start, and five weeks before trial actually began, the prosecution gave notice that it would call a different § 1108 witness — Canadian resident Kathleen J. In 2021 Kathleen J. reported to Toronto police an incident she said occurred more than two decades earlier, in 2000. The prosecution disclosed to the defense videotape interviews Toronto police had performed. After reviewing these videotapes within a week, defense counsel (1) moved to exclude Kathleen J.’s testimony because he had insufficient time to prepare, (2) moved for a continuance since he had to interview numerous identified Canadian witnesses and (3) sought a subpoena to obtain documents and communications from Kathleen J. The court (1) denied the motion to exclude, (2) denied the requested continuance and (3) refused to authorize the subpoena, despite explicitly finding the requested information “could reasonably assist the defendant in preparing his defense or lead to admissible evidence.” (16-RT-808.)

These and several other issues will be discussed below. Perhaps in some cases these errors, even when considered together, would not require reversal. But the fact of the matter, as all parties below recognized, is that this case was a pure credibility contest. And as shown by the hung jury at the first trial (leaning heavily towards acquittal on every count), the objective record of jury deliberations at both trials, and the split verdicts at the second trial, this was by any measure a close case.

It is true, of course, that a defendant is not entitled to a perfect trial. He is, however, still entitled to a fair one. And for the reasons outlined above, and discussed more fully below, as to the critical credibility questions at the heart of this case, Danny Masterson received neither. Reversal is required.

STATEMENT OF APPEALABILITY

This appeal is from a post-trial judgment that finally disposes of all issues between the parties and is authorized by Penal Code § 1237(a).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On June 3, 2021 the Los Angeles County District Attorney filed a three count information against appellant Danny Masterson. (2-CT-344- 348.) The information charged as follows:

1) Count one charged a forcible rape of Jane Doe # 1 on April 25, 2003 in violation of Penal Code § 261(a)(2). (2-CT-345.)

2) Count two charged a forcible rape of Jane Doe # 2 occurring between October 1, 2003 and December 31, 2003. (2-CT-346.)

3) Count three charged a forcible rape of Jane Doe # 3 occurring between January 1, 2001 and November 30, 2001. (2-CT-347.)

As to each offense, the state added an enhancement allegation that multiple victims were involved in violation of Penal Code § 667.61(e)(4). (2-CT-344.) Appellant pled not guilty and denied the enhancing allegations.

After a nearly one-month trial, jurors began deliberating on November 16, 2022. (11-CT-3043.) Several days later the jury indicated it could not reach a verdict on any of the three counts. (11-CT-3048.) The court reinstructed jurors and replaced two jurors who tested positive for Covid. (11-CT-3048-3049.) After several additional days of deliberation, this new jury was also unable to reach a verdict on any counts and the court declared a mistrial. (11-CT-3054.) The jury was squarely leaning towards acquittal: 10-2 on count 1, 8-4 on count 2 and 7-5 on count 3. (8-RT-504.)

The state retried the case. Opening statements began on April 24, 2023. (11-CT-3257-3258.) The state rested its case on May 12, 2023 and the defense rested without calling a witness. (11-CT-3283.) Jurors deliberated all day on May 17, May 18, May 20, May 22, May 25 and May 26 and a half day on May 23. (11-CT-3288-3296.) During this more than 29 hour deliberation, jurors returned with numerous questions for the court. (11-CT-3289-3294.) On May 31, jurors hung on the count three charge, but convicted on counts one and two. (11-CT-3298-3299.)

On September 7, 2023, the court imposed a 15 year-to-life term for each of the two convictions, for a total term of 30 years to life. (12-CT3577.) Appellant filed a timely Notice of Appeal. (13-CT-3636.)

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Overview.

As relevant here, the state charged appellant with the forcible rape of complaining witnesses [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] occurring in 2003. Much of the defense case was spent eliciting how both [Jane Doe 1]’s and [Jane Doe 2]’s recollection changed over time. As noted above, the parties had very different explanations for these changes. The prosecution’s thesis was that changes in recollection like those seen here were to be expected due to the vicissitudes of memory. The defense theory was that these changes reflected a financial interest in obtaining a forcible rape conviction to reopen the civil statute of limitations and permit rape-based damage claims.

Section B of this Statement of Facts describes the early police investigation resulting in the initial decision not to prosecute the April 2003 incident involving [Jane Doe 1]. Section C discusses the rather unusual evidence showing the complaining witnesses were very much aware not just of the statute of limitations issues in this case, but of the prosecution’s theory as to how to avoid a statute of limitations bar. Sections D and E detail the testimony given by [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] at the second trial; in light of the defense theory (that [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] changed their testimony over time), these sections also detail the prior statements they gave to police, prosecutors and friends. Section F recounts the prosecution’s remaining evidence. Finally, section G describes the extended jury deliberations at the first and second trials.

B. After An Initial Investigation Fails To Support [Jane Doe 1]’s Claims, The Prosecution Decides Not To Prosecute.

On April 25, 2003, [Jane Doe 1] and appellant had sexual relations. 14 months later — on June 6, 2004 — [Jane Doe 1] reported to police that this was rape, giving a detailed statement to Officer Schlegel. (8-CT-2289-2294; 30-RT2906-2917.) The details of [Jane Doe 1]’s initial version of events will be discussed in greater detail in section D below. Suffice it to say here, [Jane Doe 1] told police (1) she knew appellant socially and had consensual intercourse with him on a prior occasion (September 2002), (2) after going out to a club on the evening of April 24, 2003 she went to a party at appellant’s house, had a drink, felt sick and vomited, (3) appellant put her to sleep in his bed and (4) she woke up with him having sex with her. (8-CT-2290-2293; 30-RT2906-2914.) When [Jane Doe 1] resisted, appellant choked her until she passed out; when she woke up the next morning she did not recall anything but “she began to remember more and more as the day went by.” (8-CT-2293; See 30-RT-2914.)

In her June 2004 report to police, [Jane Doe 1] said there were six witnesses: B.S., L.W., J.D., J.W., S.F. and J.S. (8-CT-2290; 30-RT-2914-2915.) [Jane Doe 1] told Officer Schlegel that although she told her friend B.S. about having sex with appellant, she ([Jane Doe 1]) did not tell B.S. it was rape. (8-CT-2293.) But she told Officer Schlegel she had told another friend, S.F., that it was rape. (8-CT-2293.) [Jane Doe 1] explained she had substantial bruising on her body, so much so that her parents noticed “the bruises and asked her about them.” (8-CT-2294; See 30-RT-2915.)

Police immediately contacted [Jane Doe 1]’s father, [Father Doe], as well as witnesses J.W., L.W. and B.S. (8-CT-2315-2317.) B.S. provided names of several other potential witnesses, including Ben. S. and P.D., who police also interviewed. (8-CT-2295, 2307, 2316, 2318.) Every one of these witnesses — including [Jane Doe 1]’s own father — undercut the version of events [Jane Doe 1] gave to police. Some of them in remarkable fashion. In brief, here is what police learned from interviewing the witnesses [Jane Doe 1] herself had named:

— [Father Doe], [Jane Doe 1]’s father. Despite [Jane Doe 1]’s assurance that her parents both saw and asked about the substantial bruising on her neck, arms and thighs, [Jane Doe 1]’s father [Father Doe] told police “he had not seen [any] injuries.” (8-CT-2317.) Police asked [Father Doe] to have his wife ([Jane Doe 1]’s mother) call them. (Ibid.) She never called. (Ibid.)

— J.W. J.W. drove [Jane Doe 1] to appellant’s house on the evening of April 24. On the car ride there, and referring to her September 2002 sex with appellant, [Jane Doe 1] said “‘I’ve got to tell you, he is the best sex I've ever had.’” (8-CT-2315.)

— L.W. L.W. was appellant’s best friend, he knew [Jane Doe 1] for several years and was at the house that night. (8-CT-2316.) Earlier on the evening of April 24, [Jane Doe 1] was “coming on to him by putting her breasts in his face” and after appellant and [Jane Doe 1] went upstairs, he heard “moaning and thought to himself, ‘that could have been me having sex with [Jane Doe 1].’” (8-CT2316-2317.) He heard noises from the bedroom — “‘Ooohs’ and ‘Yes’” — which sounded like [Jane Doe 1] and appellant were having a good time. (Ibid.) Later he heard conversation but he could not hear what was being said. (Ibid.)

— Ben S. Ben S. worked for [Jane Doe 1]’s parents for years and had been friends with [Jane Doe 1] for 15 years; he was also friends with appellant. (8-CT-2318.) He saw [Jane Doe 1] the morning after she and appellant had sex; [Jane Doe 1] said “that [B.S.] was supposed to pick her up the night before, from Danny’s house. [Jane Doe 1] was ‘freaked out that (B.S.) would be pissed off at her.’ [Jane Doe 1] told him that she slept with Danny. [Ben S.] told her ‘I can’t believe you did that.’ [Jane Doe 1] smiled. She wanted advice on what she should do about [B.S.]” (8-CT-2318.)

— B.S. In June 2003 B.S. and [Jane Doe 1] spoke about the April 2003 incident when they were in New York together. (8-CT-2315.) B.S. and [Jane Doe 1] “had a long talk and [Jane Doe 1] admitted she had sexual intercourse with Danny (on April 25, 2003) and did not say it was forced.” (Ibid.)

— P.D. P.D. knew both [Jane Doe 1] and defendant for “four or five years.” (8-CT-2316.) In July 2003, P.D. asked [Jane Doe 1] “why she had sex with Danny a second time after there had been so much drama surrounding the first time they had sex with each other. [Jane Doe 1] explained that on both occasions it had been the best sex she had ever had. [P.D.] was curious and asked her why it was the best sex . . . and [Jane Doe 1] said ‘I don’t know. The positions he had me in . . . The speed . . . I finished three times.’ [P.D.] asked what she meant by ‘finished’ and [Jane Doe 1] explained she meant having an orgasm.” (Ibid.)

Police referred the matter to the District Attorney. (8-CT-2318.) After reviewing the police interviews described in summary above, in late June 2004 the District Attorney elected not to file charges. (8-CT-2309- 2310.)

C. [Jane Doe 1] And [Jane Doe 2] Are Made Aware Of The Statute Of Limitations Issues.

In a March 2017 recorded telephone call, [Jane Doe 1] and her mother spoke about the statute of limitations issues. [Jane Doe 1] noted that although “what happened to me was a long time ago” her mother had not “put two and two together” and “there’s a reason the statute [of limitations] was reopened.” 29 (8-CT-2381.) [Jane Doe 1] explained that “collusion is how they reopened my case.” (Ibid.) And a subsequent text from [Jane Doe 1] to Detective Vargas in January 2019 shows [Jane Doe 1] had been made aware of the specific requirements needed under § 667.61 to bypass the statute of limitations:

Ugh. I was told she [JD-2] and JD-3 are both out of the case. And that means 667.61 is out and therefore statute is an issue and my case can’t go forward. Please please call JD-5. Apparently a call from you, Mueller, or BOTH will likely result in her being able to agree to continue on with case.

(8-CT-2275; 9-CT-2413.)

[Jane Doe 2] was equally aware of statute of limitations concerns. Thus, in a May 2017 recorded interview, prosecutor Mueller explained to [Jane Doe 2] that because of the “passage of time” there were “statute of limitations issues.” (8-CT-2384; 9-CT-2525.) Prosecutor Mueller informed [Jane Doe 2] that resolution of these statute of limitations issues would depend “on certain acts that were done, and how they were done, and, you know, the fact that we potentially (UI) . . .” (8-CT-2384.) At that point, the audio of this recorded explanation of the statute of limitations abruptly ends. (Ibid.)

D. [Jane Doe 1]’s Evolving Versions.

16 years after the 2004 decision not to prosecute, the prosecution filed charges in connection with [Jane Doe 1]’s allegations. Although the case was tried twice, neither jury ever heard from the witnesses police interviewed back in 2004 after the report was first made: [Father Doe], J.W., L.W., Ben S., B.S. or P.D. What they did hear, however, was that [Jane Doe 1]’s versions of events changed dramatically over time, not only in connection with [Jane Doe 1]’s testimony about the April 2003 charged incident, but as to the prior intercourse in September 2002 as well.

1. Version 1: the June 2004 story as told to Detective Schlegel.

[Jane Doe 1] spoke to Officer Schlegel in June 2004. With respect to the prior sexual contact in September 2002, [Jane Doe 1] admitted she had “consensual sexual intercourse” with appellant prior to the April 25 incident. (26-RT2211; 30-RT-2938-2939; 8-CT-2293.) [Jane Doe 1] explained that during the September encounter — which involved vaginal intercourse — appellant “tried to enter her anus . . . but she refused.” (8-CT-2293.) Because she refused [Jane Doe 1] made no mention of other injuries such as pain or bleeding. (30-RT-2938-2939; 8-CT-2293.)

With respect to the April 2003 charged rape, [Jane Doe 1] told Officer Schlegel that on April 24, 2003 she went to a club with friends. (30-RT2909; 8-CT-2290.) After clubbing, they went to a party at appellant’s home. (30-RT-2909; 8-CT-2290.) Once there, she and appellant went to the kitchen together where he made her a drink. (30-RT-2924; 8-CT-2290.)

[Jane Doe 1] took her drink outside to speak with Luke Watson, then “wandered” into the back yard where appellant was in the jacuzzi with several women. (30-RT-2925; 8-CT-2290.) He pulled her into the jacuzzi. (30-RT-2910; 8-CT-2290.) When [Jane Doe 1] started to feel nauseous, appellant “guided her up the stairs” towards the bathroom and held on to her so that “she wouldn’t fall down.” (8-CT-2290-2291; See 30-RT-2925-2926.) There was no mention of calling her father or leaving a voice message for him. (30-RT-2926.) Once upstairs, [Jane Doe 1] vomited into the toilet but also on herself. (30-RT-2911; 8-CT-2291.) Appellant put her into the shower. (30-RT-2911; 8-CT-2291.)

[Jane Doe 1] told police that appellant carried her into his bedroom and put her in bed where she fell asleep. (30-RT-2911-2912; 8-CT-2292.) She woke up to appellant on top of her having sex. (30-RT-2912; 8-CT-2292.) She pushed a pillow in his face to try and get him to stop; he took the pillow and pushed it into her face. (30-RT-2912; 8-CT-2292.) [Jane Doe 1] could not breathe and thought she was going to “die.” (30-RT-2912; 8-CT-2292.) As she tried to find something to hit appellant with, he placed his left hand around her throat and choked her until she passed out. (30-RT-2913; 8-CT2292.)

When [Jane Doe 1] woke up, appellant was gone so she crawled into the closet. (30-RT-2913; 8-CT-2292.) Later, he picked her up and put her back in the bed where she fell asleep. (30-RT-2913; 8-CT-2293.) [Jane Doe 1] “didn’t remember anything [that] morning . . . [but] she began to remember more and more as the day went by.” (8-CT-2293; See 30-RT-2914.)

2. Version 2: the June 2004 story as told to Detective Myers.

Several days later, [Jane Doe 1] spoke with Detective Myers. As to the prior September 2002 incident, and just as she told Officer Schlegel, [Jane Doe 1] said she had “consensual sexual intercourse” with appellant previously. (8-CT2304; See 31-RT-3078.) Similarly, and again just as she told Officer Schlegel, [Jane Doe 1] explained that during the September incident, appellant “attempted” anal sex, she “pulled herself away,” he immediately “apologized” and she thought the contact may have been “accidental.” (8- CT-2304; See 30-RT-2938-2939 [sex was consensual]; 31-RT-3150 [appellant apologized for the anal contact]; 31-RT-3078 [appellant’s penis “touched” her anus].) Yet again, because she had “pulled herself away,” [Jane Doe 1] did not report any pain or bleeding. (8-CT-2304.)

As to the April 2003 charged offense, and in contrast to Version 1, [Jane Doe 1] now said that appellant was alone in the kitchen when he made her a drink and he brought it to her. (31-RT-3085; 8-CT-2313-2314.) And because (in contrast to Version 1) [Jane Doe 1] was no longer with appellant when the drink was made, [Jane Doe 1] now theorized he might have put a “date rape type drug” into her drink. (31-RT-3085; 8-CT-2313-2314.)

[Jane Doe 1] repeated to Detective Myers what she had told Officer Schlegel — she “wandered” into the back yard area where appellant was in the jacuzzi. (30-RT-2910, 2925; 31-RT-3080-3081.) But in contrast to Version 1, when she began to feel sick in the jacuzzi, appellant did not “guide” [Jane Doe 1] up the stairs; instead, he “picked her up and carried her upstairs to go throw up.” (31-RT-3087; 8-CT-2305.) Again, she made no mention of calling her father or leaving him a voice mail as she was carried upstairs. (31-RT-3082.)

3. Version 3: the January 2017 story as told to Detective Myape.

In January 2017 — over 12 years after giving her first two versions of events — [Jane Doe 1] spoke with Detective Myape. As to the September 2002 incident, the fleeting anal contact [Jane Doe 1] had described in Version 1, and characterized as “accidental” in Version 2 — and for which appellant had immediately apologized — evolved into appellant “attempting” anal sex, stopping once she told him to stop. (8-CT-2349.) But in Version 3 it did not go beyond this, and because this was merely an attempt at anal intercourse, [Jane Doe 1] again reported no pain or anal bleeding. (31-RT-3035.) [2. During the course of the two trials Detective Myape’s name changed to Detective Reyes. To avoid confusion, appellant will consistently refer to her as Detective Myape.]

[Jane Doe 1]’s interview with Detective Myape also covered the April 2003 charged offense. But this version had a number of facts which [Jane Doe 1] had never mentioned in either of her first two versions:

— For the first time, [Jane Doe 1] said that when appellant carried her upstairs she was “freaking out” and so she called her father “crying” for help. (1-CTO-193, 195.) [3. “1 CTO” refers to Volume 1 of a two-volume, 351-page Clerk’s Transcript filed with this Court on May 13, 2024 entitled “Clerk’s Transcript Omission.”] When her father did not answer, she left him a voice mail. (4-CT-917-918.) [4. Because [Jane Doe 1]’s recollection that she made a telephone call to her father did not occur until 2017, seven years after her father passed away (20-RT-1368), there was no way to test [Jane Doe 1]’s recent recollection.]

— For the first time, [Jane Doe 1] said that appellant displayed a gun during the sexual assault. (31-RT-3036; 8-CT-2348.) [5. At trial, [Jane Doe 1] claimed she actually did tell police about the gun in her initial interviews. (25-RT-2138.) But Officer Schlegel was clear that it had not been discussed at his June 4, 2004 interview or it surely would have made it into this report. (30-RT-2912, 2936-2937.) And Detective Myers was equally clear; if [Jane Doe 1] had mentioned a gun, it would have appeared in the police report. (31-RT-3084-3085.)]

In this version, and just as she told Detective Myers in Version 2, appellant was alone in the house when he made [Jane Doe 1] a drink and he brought it to her outside. (1-CTO-181-183.) As for getting into the jacuzzi, now appellant pulled her by her wrist and threw her in. (1-CTO-185.)

4. Version 4: the April 2017 story as told to prosecutor Mueller.

Four months later — in April 2017 — [Jane Doe 1] spoke with prosecutor Mueller. As to the September 2002 incident, [Jane Doe 1] explained (as in Versions 1, 2 and 3), that the sexual intercourse was consensual. (26-RT-2224- 2226). But as to the anal contact, the story began to shift again.

Recall that in Version 1, [Jane Doe 1] said she “refused” anal sex and that was the end of it. In Version 2, she said she thought the fleeting anal contact was “accidental,” noting that after she refused, appellant immediately apologized. In Version 3, appellant intentionally tried to insert his penis into [Jane Doe 1]’s anus, and she told him to stop. Now, in Version 4, [Jane Doe 1] claimed appellant had penetrated her anally. (8-CT-2284.) And for the very first time, [Jane Doe 1] recalled (1) she had to “fight him” to get appellant to stop, (2) this caused her to pull a muscle in her back and (3) the incident had become “so traumatic to me.” (8-CT-2284.) Although in Version 4 [Jane Doe 1] talked about the pain the anal penetration caused her (the pulled muscle), she said nothing about any other pain or bleeding. At the May 2021 preliminary hearing, [Jane Doe 1] returned to this version of the story, testifying that she had to “fight[] him off . . . and was incredibly upset.” And now the contact was “not consensual.” (5-ART-(8/23/24)-1011, 1018.) [6. “5-ART-(8/23/24)” refers to Volume 5 of the 17-volume Augmented Reporter’s Transcript filed with the Court on August 23, 2024. References to “ART-(5/17/24)” refer to the 25-volume Augmented Reporter’s Transcript filed with the Court on May 17, 2024.]

Nothing about this interview in the appellate record addresses (1) how [Jane Doe 1] got in the jacuzzi, (2) whether she walked or was carried upstairs to the bathroom, (3) whether [Jane Doe 1] telephoned her father for help as she went up the stairs and/or (4) whether appellant pulled out a gun in the bedroom. Nor does anything in the record about this interview address the conflicting accounts (between Versions 1 and 2) of where [Jane Doe 1] was when her drink was made.

But four years later, during the 2021 preliminary hearing, [Jane Doe 1] offered yet another version. [Jane Doe 1] admitted telling Church officials not only that she was with appellant when her drink was poured (in accord with Version 1 but in contrast to Version 2), but that she herself actually made her own drink. (5-ART-(8/23/24)-1098-1099.) She would not repeat that particular version again.

5. Version 5: the 2022 story as told to the first jury.

The first trial began in 2022. With respect to the September 2002 incident, and in contrast to Versions 1, 2, 3 and 4, [Jane Doe 1] now claimed the September 2002 sexual intercourse was not consensual, but was rape. (6- ART-(5/17/24)-837.) As for the anal contact, [Jane Doe 1] mirrored Version 3 told in 2017 to Detective Myape that when appellant started to penetrate her anus, she pulled away and screamed “no” after which he stopped. (4-ART- (5/17/24)-577.) To this version, she added that it was painful but again said nothing about bleeding. (4-ART-(5/17/24)-577-579.)

As to the charged April 2003 incident, [Jane Doe 1]’s Version 5 added two main new twists to the narrative.

The first has to do with how [Jane Doe 1] got into the jacuzzi. Recall that in Versions 1 and 2, [Jane Doe 1] said that after getting her drink she “wandered” into the back yard area where appellant was in the jacuzzi. (8-CT-2290; 30-RT2910, 2925.)

But in Version 5, [Jane Doe 1] told jurors a very different story, a story much more consistent with the use of force by appellant. Now [Jane Doe 1] had not walked over to the jacuzzi on her own; instead, appellant found her inside the home, grabbed her wrists and “drag[ged]” her towards the door leading outside. (5-ART-(5/17/24)-649.) In an effort to stop him, [Jane Doe 1] used her body weight as “resistance” and “tried to sit on the floor.” (5-ART- (5/17/24)-649.) When he still would not release her, she went “along with him because it hurt[].” (5-ART-(5/17/24)-649.) [Jane Doe 1] was telling appellant 37 “no, no, please” but he picked her up anyway and carried her through the back door and into the back yard. (5-ART-(5/17/24)-653-654.) [Jane Doe 1] continued to say “no, no” as appellant removed her pants and threw her in the jacuzzi. (5-ART-(5/17/24)-655.)

Second, [Jane Doe 1] added substantially to facts she had for the first time added in Version 3. It was in Version 3 that [Jane Doe 1] said, for the first time, that she telephoned her father as appellant carried her upstairs and, when he did not answer, she left him a voice mail. (4-CT-917-918; 1-CTO-193, 195.) Now, [Jane Doe 1] added that (1) she tried to send her father a text message saying “help” but (2) Luke Watson took her phone away before she could push send. (7-ART-(5/17/24)-1053.)

As to two other important facts — the drink at appellant’s home and his use of a gun — [Jane Doe 1]’s testimony matched some but obviously not all of her prior versions. Thus, recall that in Version 1, [Jane Doe 1] said she was with appellant in the kitchen when he made her a drink. (8-CT-2290.) In Version 2, she was not with him when he made the drink, but he brought it to her outside. (8-CT-2313-2314.) At the preliminary hearing, [Jane Doe 1] admitted telling Church officials she was with appellant and she poured her own drink. (5 ART (8/3/24) 1098-1099.) [Jane Doe 1] stuck with Version 2 at the first trial. (6-ART-(5/17/24)-902-903.)

As for the use of a gun, the testimony in Version 5 remained in line with her description to Detective Myape in Version 3. (5-ART-(5/17/24)- 688.) [Jane Doe 1] testified she heard a “noise from the door. A man’s voice yelling.” (5-ART-(5/17/24)-688.) Appellant pulled out a gun from inside his bedside table. (5-ART-(5/17/24)-688.) He then dropped it back into the drawer and when [Jane Doe 1] reached for it he “slam[med] it really hard” on her hand. (5-ART-(5/17/24)-688.)

6. Version 6: the 2023 story as told to the second jury.

At the second trial, [Jane Doe 1] testified about both the September 2002 and April 2003 incidents. In contrast to Versions 1, 2, 3 and 4 (but in accord with Version 5), [Jane Doe 1] claimed the September 2002 intercourse was also rape. (26-RT-2191.) After the vaginal rape, appellant then penetrated her anally. (24-RT-1928-1931.)

But for the very first time, [Jane Doe 1] recalled that this anal penetration caused a very sharp stabbing pain which [Jane Doe 1] now recalled and described as “the sharpest pain I’ve ever experienced.” (24-RT-1929-1930.) For the very first time, [Jane Doe 1] said that for days she experienced bleeding from her anus, discharge when she went to the bathroom, and burning. (24-RT1933-1934.) For the very first time, [Jane Doe 1] testified “[her anus] was really injured, and [she] was in a lot of pain.” (26-RT-2229-2230.) In her previous statements to (1) Officer Schlegel, (2) Detective Myers, and (3) Detective Myape, [Jane Doe 1] had never mentioned her anus was “really injured” or that it was the “sharpest pain she had ever experienced.”

[Jane Doe 1] then testified about the April 2003 charged rape. As noted, prior to the first trial [Jane Doe 1] offered three different versions of how she got a drink that evening: she was with appellant in the kitchen when he prepared the drink, he made her the drink and brought it out to her and she poured the drink herself. At the second trial, like the first, [Jane Doe 1] testified that when appellant asked her what she wanted to drink, she said “I don’t know, vodka something” and he returned with a drink for her. (24-RT-1965-1966.)

In Versions 1 and 2, [Jane Doe 1] walked to the jacuzzi. But in Version 6 (as in Version 5), appellant forcibly dragged her from the house into the jacuzzi. (26-RT-2263-2264). When she resisted, he picked her up and carried her to the jacuzzi. (26-RT-2267.)

[Jane Doe 1] started to feel ill while she was in the jacuzzi. (24-RT-1976- 1977.) In Version 1, [Jane Doe 1] told police appellant “guided her” up the stairs to get to the bathroom. (8-CT-2290-2291; See 30-RT-2925-2926.) But in Version 6 (as in Versions 2 and 5), [Jane Doe 1] told jurors appellant forcibly carried her upstairs. (26-RT-2281.) As she was being carried up the stairs, she telephoned her father for help; when he did not answer, she left a voice mail. (26-RT-2282.)

Upstairs, appellant took [Jane Doe 1] to the bathroom where he helped her to throw up. (25-RT-2012-2013.) [Jane Doe 1] testified that when she threw up in her hair, appellant “drag[ged]” her into the shower. (25-RT-2012-2014) He soaped her breasts and body then picked her up and put her in his bed. (25- RT-2015-2017.)

As for the sexual assault itself, [Jane Doe 1] testified that when she woke up appellant was penetrating her vagina with his penis. (25-RT-2018.) [Jane Doe 1] grabbed a pillow and tried to push him away but he pushed it back into her face and she passed out again. (25-RT-2019-2021.) When [Jane Doe 1] regained consciousness she grabbed for appellant’s neck to push him away. (25-RT2022.) He then grabbed her neck and she thought “that’s the last face I will see.” (25-RT-2023-2024.)

In Version 6 (and generally consistent with Versions 3 and 5), [Jane Doe 1] testified that during the sexual assault, someone came to the door and she heard a male voice. (25-RT-2025.) Appellant reached into his night stand and pulled out a gun. (25-RT-2027.) Although he did not point the gun directly at her, he was agitated and told [Jane Doe 1] to “shut the fuck up”; he then put the gun back into the drawer. (25-RT-2028-2029.) When [Jane Doe 1] tried to grab the gun which was now in the drawer, appellant slammed the drawer shut on her hand. (25-RT-2029.)

The next morning, [Jane Doe 1] had “no memory” of anything that had occurred. (25-RT-2035.) Luke Watson was downstairs and put [Jane Doe 1] in a cab; she went to her house because she was late for her father’s birthday party and she and her family were leaving for Florida that evening. (25-RT2036-2038, 2041.) Later that day, “flashes” of her memory started to return to her. (25-RT-2049.) About 24 hours after the assault, [Jane Doe 1] started to bruise. (25-RT-2052-2054.) The bruising continued to get worse showing up on her hips, forearm, hands, inside of thighs, legs, and neck. (25-RT2055-2058.)

Of course, in Version 1, [Jane Doe 1] told police that her parents noticed “the bruises and asked her about them.” (8-CT-2294.) But when police contacted her father, he undercut [Jane Doe 1]’s version of events, telling them “he had not seen [any] injuries.” (8-CT-2317.) Police asked [Father Doe] to have his wife ([Jane Doe 1]’s mother) call them. (Ibid.) She never called. (Ibid.)

In Version 6, the story changed. Now, [Jane Doe 1] testified it was only her mother who noticed the bruising. (25-RT-2052-2054.) [Jane Doe 1] told her mother that she did not know what the bruising was from. (25-RT-2054.)

E. [Jane Doe 2]’s Evolving Versions.

In October 2003, appellant invited [Jane Doe 2] to his home for a swim. They had sex that night and then talked for hours. As [Jane Doe 2] would later admit, she hoped appellant would ask her for another date. But he did not. More than 13 years later, in January 2017, [Jane Doe 2] reported to police for the first time that she had been raped.

[Jane Doe 2] gave a detailed statement to Detective Myape. (29-RT-2695.) As with [Jane Doe 1], [Jane Doe 2]’s version of events also changed in critical respects between her report to police and the two trials.

As with [Jane Doe 1], there were certain undisputed facts. [Jane Doe 2] was an aspiring actress who knew appellant through their common membership in the Church of Scientology. (28-RT-2514-2515.) They met in 1999 or 2000 and were friendly at parties they both attended. (28-RT-2515, 2534.)

At the time, [Jane Doe 2] had problems with anxiety. (28-RT-2525.) She admitted she often drank alcohol before social engagements to “take the edge off” and she would “get drunk” which impacted her memory. (28-RT2527; 29-RT-2651-2652.)

In October 2003, [Jane Doe 2]’s roommate invited her to go out for drinks with appellant and his friend Luke Watson. (28-RT-2523-2524.) Because [Jane Doe 2] was “nervous” about this date, [Jane Doe 2] drank beforehand. (28-RT-2525, 2527.) At the end of the night, [Jane Doe 2] was flattered when appellant asked for her phone number. (28-RT-2532.)

Several days later, appellant invited [Jane Doe 2] to his house for a swim. (28-RT-2533-2535.) [Jane Doe 2] agreed but told him she was not going swimming. (28-RT-2535-2537.) Although appellant was “not [her] type,” [Jane Doe 2] was “flattered” to be invited and “intrigued.” (28-RT-2535-2538.)

Because she was nervous, she drank alcohol “to take the edge off” before walking over. (28-RT-2538.) Once she arrived, they had a drink, talked and walked out to the jacuzzi. (28-RT-2542-2546.) Appellant told her to “take off your clothes now . . . . You’re getting in the water.” [Jane Doe 2] was “giggling” and telling him “I’m not going in the pool.” (28-RT-2547.) [Jane Doe 2] could not recall how she got into the jacuzzi and things started to go “black.” (28-RT-2547.) Appellant kissed her “intensely” and may have put his finger in her vagina. (28-RT-2549.) After they got out of the jacuzzi, they went upstairs to his bathroom and into the shower. (28-RT-2555- 2556.) [Jane Doe 2] told appellant that while kissing and other acts were fine, “we can’t have sex.” (28-RT-2563.)

In the shower, they kissed, appellant put his fingers in her vagina, and then quickly put his penis in her vagina. (28-RT-2557.) [Jane Doe 2] pushed him away and said “what are you doing? No. I told you no.” (28-RT2557-2558.) Appellant said “OK” and stopped. (28-RT-2558.) After the shower, they got into bed, where there was “heavy kissing,” and [Jane Doe 2] told him “we can’t have sex.” (28-RT-2563.)

Appellant performed oral sex and [Jane Doe 2] believed she did the same. (28-RT-2564; 29-RT-2691.) According to [Jane Doe 2], appellant then flipped her so that she was on her hands and knees and put his penis in her vagina. (28- RT-2565-2566.) His penis was hitting her cervix and it was painful. (28- RT-2566.) [Jane Doe 2] told appellant that if he was not going to listen to her, he could at least put a condom on. (28-RT-2567.) Appellant did not threaten her, use a weapon or hit her. (28-RT-2577.) Afterward, they talked sitting “facing each other” on the bed for several hours until 5 or 6 a.m. (28-RT2581, 2584.) [Jane Doe 2] described it as “almost romantic” and they shared with each other that they were “both passionate people.” (28-RT-2581; 29-RT2699.) [Jane Doe 2] then walked home. (28-RT-2584.)

[Jane Doe 2] was candid. After she went home, [Jane Doe 2] waited for appellant to call her for another date. After four or five days without a call, [Jane Doe 2] called and said “I thought you were going to call me. . . . I thought you liked me, and I like you.” (28-RT-2585.) She thought he would fall in love with her. (29-RT-2700.) Instead, his responses were “short” and he said he was busy. (28-RT-2585-2586; 29-RT-2702-2703.)

At some point, [Jane Doe 2] called again because she was romantically interested in a man appellant knew and wanted a set up because appellant “owe[d]” her. (28-RT-2587.) Appellant refused. (28-RT-2587.) In 2006 or 2007, [Jane Doe 2] called yet again, this time because she was working for an art dealer and thought appellant might be interested in purchasing some high end art. (28-RT-2588-2589.) Appellant once again rebuffed her and said no. (28-RT-2589.) Finally, [Jane Doe 2] saw appellant at a party in 2008 and asked about their mutual friend Ilaria. (28-RT-2589-2590.) He simply answered that Ilaria was “fine.” (28-RT-2590.) That was their only contact that night. (28-RT-2590.)

While this part of the story remained consistent, there were critical aspects that evolved over time. [Jane Doe 2] spoke to her mother [Mother Doe], friends Jordan Ladd, Rachel Smith, Mariah O’Brien, Detective Esther Myape and testified at the preliminary hearing and both trials.

1. Version 1: the 2003 story as told to her mother [Mother Doe], and friends Jordan Ladd and Rachel Smith.

Sometime after the 2003 encounter with appellant, and the telephone call where she expressed her confusion over not hearing from him, [Jane Doe 2] spoke with her mother [Mother Doe]. [Jane Doe 2] explained that she had had “rough” sex with appellant and her relationship with him was not “going well.” (28-RT-2594-2595.) [Jane Doe 2] did not say that appellant had raped her. (28-RT-2595.) Instead, [Mother Doe] recalled [Jane Doe 2] being “unhappy” about how appellant treated her. (30-RT-2893.) [Jane Doe 2] said alcohol was involved but never mentioned the possibility of being drugged. (30-RT-2892.)

According to [Jane Doe 2], she soon told her friends Jordan Ladd and Rachel Smith about sex with appellant. Again, she did not tell either of them she was raped. (28-RT-2604-2607.) Instead, [Jane Doe 2] told Ladd he came at her like a “jack hammer.” (28-RT-2605.) She told Smith the sex with appellant was “forceful and jarring.” (28-RT-2607.) [Jane Doe 2] did not tell her mother, Ladd or Smith she had been afraid of appellant nor that there were multiple sex acts after having sex on the bed.

For their parts, Smith and Ladd confirmed [Jane Doe 2] told them about sex with appellant, but never used the word “rape.” (29-RT-2743, 2771.) Smith sought to explain [Jane Doe 2] would not use the word “rape” since that reflected a “victim mentality.” (29-RT-2743-2744.) And Ladd offered that [Jane Doe 2] “begged [appellant] to stop” and she (Ladd) therefore viewed it as rape. (27-RT-2770-2771.)

2. Version 2: the 2011-2013 story as told to Mariah O’Brien.

At some point between 2011 and 2013, [Jane Doe 2] spoke with her friend Mariah O’Brien. O’Brien had been a member of the Church of Scientology from the 1990s until 2012 and was in the same “friend group” as appellant. (30-RT-2846-2847.) [Jane Doe 2] told O’Brien that she and appellant had gone on a “date.” (30-RT-2858.) [Jane Doe 2] never mentioned drugging. (30-RT-2859.) [Jane Doe 2] did not say she was afraid of appellant or that they had engaged in multiple sex acts after having sex on the bed

3. Version 3: the 2014 story as told to Mariah O’Brien.

In 2014, Ms. O’Brien invited [Jane Doe 2] to her home for dinner. [Jane Doe 2] was talking with another friend Jordana Shapiro. Ms. O’Brien could not hear what they were talking about specifically but [Jane Doe 2] stood up at the table and accused appellant of rape. (30-RT-2850.) Because Ms. O’Brien’s young children were also at the table, she became upset and asked [Jane Doe 2] to leave. (30-RT-2850-2851.) Ms. O’Brien testified they had not spoken since. (30- RT-2851.) [7. In late 2016, [Jane Doe 3] contacted O’Brien, asking if she knew of any other women claiming appellant had assaulted them. (30-RT-2852-2853.) When O’Brien said [Jane Doe 2] had made such a claim, [Jane Doe 3] contacted [Jane Doe 2]. (28-RT2610-2612, 2614-2615; 30-RT-2852-2853.) It was not until [Jane Doe 3] asked [Jane Doe 2] to contact police that [Jane Doe 2] reported to police in 2017. (28-RT-2615.)]

4. Version 4: the January 2017 story as told to Detective Myape.

As noted above, [Jane Doe 2] reported a sexual assault to police in January 2017. She spoke with Detective Myape. (29-RT-2695.) [Jane Doe 2] explained that prior to meeting up with appellant that night, she “wanted him to kiss [her]. [She] wanted it to be romantic.” (9-CT-2459.) While the sexual encounter was occurring [Jane Doe 2] thought “What if this is just dominant sex and he really likes me and I’m just drunk.” (29-RT-2694.) [Jane Doe 2] was clear; she did not fear appellant was going to “hurt [her] or hit [her].” (28-RT-2635- 2636.)

With respect to alcohol consumption that night, [Jane Doe 2] said that before going to appellant’s house she had “a little bit of vodka and maybe one or two glasses of wine.” (29-RT-2668-2669.) She knew she “drank before [she] got to him because [she] was so nervous to go there.” (9-CT-2463.) Once there, she was not sure how much she had to drink. (29-RT-2668- 2669.) [Jane Doe 2] explained she was “drunk.” (29-RT-2696-2697.) In the January 2017 interview, and for the first time, [Jane Doe 2] said appellant might have drugged her. (29-RT-2719-2720.) Once again, [Jane Doe 2] did not mention that other sex acts occurred after they had sex on the bed.

5. Version 5: the May 2017 story as told to prosecutor Mueller.

[Jane Doe 2] spoke with prosecutor Mueller in May 2017. As noted above, [Jane Doe 2] testified that after she and appellant were in the jacuzzi they went upstairs to shower together. [Jane Doe 2] told Mueller she could not recall whether the shower was his idea or hers. (29-RT-2682-2683.) As for the shower itself, when appellant entered her she concluded “he fucked up [and] . . . [h]e should not have done that, but we can manage, and . . . we’ll just kiss and make out . . . .” (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1614.)

And that they certainly did, as [Jane Doe 2] candidly explained to prosecutor Mueller. [Jane Doe 2] described that once in the bedroom she “was getting into it with him.” (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1613.)

[Jane Doe 2] made no mention of her alcohol consumption before arriving at appellant’s home, being afraid of appellant or other sex acts which occurred after they had sex on the bed.

6. Version 6: the story as told at the 2021 preliminary hearing.

At the preliminary hearing, [Jane Doe 2] testified that before coming over she had “maybe a little vodka . . . maybe a little wine.” (7-ART-(8/23/24)- 48 1554.) Once at his home, [Jane Doe 2] had “a glass of red wine” but could not remember if she drank more than one. (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1583-1584.) [Jane Doe 2] testified that after intercourse in the bed, she did not recall any additional sexual contact between them that night. (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1571.) [Jane Doe 2] thought they would “probably start dating.” (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1626-1627.) In fact, they talked on his bed and then on the terrace for “a couple of hours” about all kinds of “different things” after having sex. (7-ART- (8/23/24)-1570-1571.)

Two important areas of her testimony had radically changed however. First, in stark contrast to Version 4 — where [Jane Doe 2] told Detective Myape she did not fear appellant was going to “hurt [her] or hit [her]” — she now testified she did fear he would “hit [her] or hurt her” and she did not physically resist because she was “afraid that it could escalate to violence.” (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1620-1621.) Second, in contrast to Version 5 — where she could not recall whose idea it was to shower together — she now recalled appellant “ordering [her] to go upstairs to his shower.” (7-ART-(8/23/24)- 1559.)

7. Version 7: the story as told at the 2023 trial.

With respect to alcohol consumption, [Jane Doe 2]’s story had evolved. In Versions 1 and 2 she told her mother, and friends, that alcohol was involved that evening. And in Version 4, she told Detective Myape that (1) before heading to appellant’s home that evening, she drank vodka and two glasses of wine and (2) after arriving she had more to drink, though she did not recall how much. In Version 6 (the preliminary hearing) she said that before going over she had “maybe a little vodka . . . maybe a little wine” and once there she drank “a glass of red wine” but could not remember if she drank more than one. (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1554, 1583-1584.) Now however, [Jane Doe 2] testified she only had “two or three . . . sips” of alcohol before arriving at appellant’s home. (28-RT-2538-2539.) And once there, she only drank “a few sips . . . [n]ot two sips, not ten.” (28-RT-2544.)

In this version, [Jane Doe 2]’s expectations for romance also changed dramatically. In Version 4, [Jane Doe 2] told Detective Myape she “wanted him to kiss [her]. [She] wanted it to be romantic.” But [Jane Doe 2] now testified that rather than be romantic, she instead planned to “have a glass of wine and talk and . . . [go] home, and that’s it.” (28-RT-2536-2537.)

As for the shower, in her interview with prosecutor Mueller (Version 5), [Jane Doe 2] could not remember who suggested they shower together. (29-RT2682-2683.) In that version, [Jane Doe 2] said that when appellant entered her in the shower, she concluded “he fucked up [and] . . . [h]e should not have done that, but we can manage, and . . . we’ll just kiss and make out . . . .” (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1614.)

But in Version 7, [Jane Doe 2] repeated her preliminary hearing testimony (Version 6), recalling that appellant “ordered [her] to get into the shower.” (29-RT-2682.) In stark contrast to Version 4 — where [Jane Doe 2] told Detective Myape she did not fear appellant was going to “hurt [her] or hit [her]” — she now testified in line with her Version 6 preliminary hearing testimony that “I was afraid it could become physically violent if I resisted too much.” (28-RT-2577.) Now she “wasn’t pushing him” to stop because she “didn’t want him to become [violent,] to hit [her] or something.” (28-RT-2558.)

Finally, even the number of sex acts had now changed. In Version 6 [Jane Doe 2] said that after sex on the bed, she did not recall any additional sexual contact between them that night. (7-ART-(8/23/24)-1571.) But in Version 7, [Jane Doe 2] offered a very different recollection:

So I know more sexual acts happened, though I don’t like to categorize it as sex because all of it was rape. And more things happened after that that were also rape.

(28-RT-2579.)

F. The Remaining Evidence.

1. Evidence Code § 1108 evidence.

Prior to the first trial, the prosecution identified two potential § 1108 witnesses, Tricia V. and Canadian resident Kathleen J. On August 22, 2022, the prosecution gave formal notice it would call Tricia V. at trial. (9- CT-2646.) Several weeks later, the prosecution provided defense counsel with a “heavily redacted Toronto police report” regarding a 2000 incident Kathleen J. first reported to Toronto police in 2021, but explicitly advised defense counsel that “the People do not intend to call [K.J.] as a witness at trial.” (11-CT-3205 [emphasis in original]; 16-RT-810.)

At the first trial, Tricia V. testified that appellant, who she knew from working on a movie with him in 1996, raped her twice in 1996. (17-ART-(5/17/24)-2487, 2492-2508, 2550-2560.) But on cross-examination she admitted that after hearing about the charges against appellant, she sent his brother Chris a Facebook message:

[H]ey Chris, I saw a fucked up article posted about Danny. Just wanted to send you guys some support. Danny and you were, too, were [sic] so protective of me, looked out for me and put up when my BF cheated on me and I didn’t have a place to stay. Hope you are both doing well. XOX, Tricia.

(18-ART-(5/17/24)-2645; 20-ART-(5/17/24)-2919-2920.) Jurors hung on all counts.

The prosecutor did not call Tricia at the second trial. Instead, on March 6, 2023 — only weeks before the second trial was to start — the state gave notice it would be calling Kathleen J. instead. (16-RT-810.) After reviewing video recordings of witness interviews referenced in the redacted Canadian police report furnished prior to the first trial, defense counsel (1) moved to exclude Kathleen J.’s testimony because he had insufficient time to prepare to cross-examine her, (2) requested a continuance and (3) sought to subpoena any written communications she had about appellant. (1-CTO90-93; 11-CT-3215, 3218l Settled Record (“SR”) Exhibit 2 at pp. 5-6; 13- RT-630.) The trial court denied the motion to exclude and the continuance and quashed the subpoena. (11-CT-3187, 3223; 15-RT-767; 16-RT-808- 809.) [8. The five court exhibits comprising the settled record were delivered to this Court from the Superior Court on August 23, 2024 in a box containing other trial exhibits unrelated to the settled record.]

Kathleen J. testified that in 2000, she was working as an assistant prop manager on a film being shot in Canada. (31-RT-3091-3092.) At a dinner prior to the wrap party, she had two glasses of wine. (31-RT-3094.) Later she went to a party where a man offered her a vodka drink, and sat down with her on the couch to talk. (31-RT-3098-3100.) Kathleen started to feel nauseous and light headed. (31-RT-3101-3102.) She said she needed a bathroom, and the man offered to show her where it was. (31-RT3102.) Kathleen recalled walking into a bedroom with the man who then raped her. (31-RT-3102-3104.) She blacked out and her next memory was walking down the hotel hall carrying her shoes. (31-RT-3104.) She did not tell anyone about the rape. (31-RT-3106-3107.)

Five months later, Kathleen watched the movie Dracula 2000 with her husband. When she saw appellant on screen, she identified him as her assailant. (31-RT-3109-3110.) Kathleen broke down crying and told her husband what had happened. (31-RT-3110-3111.) Having just identified the man who brutally raped her, and just told her husband about the rape, Kathleen J. and her husband continued to watch the movie, later telling police “of course we watched it.” (31-RT-3130-3131.) She did not, however, call police to report the assault until nearly 21 years later when she saw the allegations against appellant. (31-RT-3113-3116.)

2. Expert testimony about date rape drugs and inconsistent testimony.

Police criminalist Jennifer Ferencz testified that the date rape drug Gamma-hyroxbutyrate (“GHB”) was odorless and colorless. (30-RT-2830.) When added to a drink, it causes euphoria and a drunk feeling. (30-RT2826.) A higher dose causes nausea, vomiting, lack of muscle control, drowsiness, dizziness, and sedation. (30-RT-2829.) The effects of GHB occur within about 10-20 minutes. (30-RT-2830-2831.) Ferencz admitted that alcohol can also cause nausea, vomiting and drowsiness. (30-RT2843.) She also admitted this was the first case in which she testified as an expert where there was no physical evidence and the only evidence of impairment was self-reported by a witness claiming impairment. (30-RT2842.) In addition to the expert testimony on date rape drugs, the prosecution responded to the evolving stories of [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2], at least in part, by offering testimony from rape trauma expert Barbara Ziv, who explained why rape victims provide inconsistent testimony. (23-RT-1802- 1803, 1806.)

3. Other evidence.

Appellant, [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] were all members of the Church of Scientology (“COS”). At both trials the prosecution offered evidence about COS tenets. The court issued very different rulings at the two trials, and allowed substantially more COS evidence at the second trial.

Because the court’s rulings are the subject of Argument VI, and to avoid duplication, the rulings and evidence relating to the COS evidence will be discussed in the context of Argument VI. Suffice it to say here that while some COS evidence was allowed at the first trial, jurors were instructed that this evidence could only be considered to assess the credibility of the complaining witnesses. (19-ART-(5/17/24)-2753.) At the second trial, not only was substantially more COS evidence permitted — including testimony from a former Scientologist testifying as an expert — but the credibility limitation on how the jury could consider that evidence was lifted, and jurors were permitted to consider the COS evidence for the truth of the matter. (33-RT-3254-3256.) In the court’s view, at the second trial this evidence was now “relevant to determining whether defendant committed the alleged crimes.” (11-CT-3175.)

Jurors also learned that Detective Myape specifically advised each of the complaining witnesses not to communicate with one another. (31-RT2995-2999.) Myape explained that the purpose of this warning was to make sure the witnesses were “not contaminating [the case by] talking with each other.” (31-RT-2998.) Myape recalled that [Jane Doe 2] responded to this advice by saying she could “pretty much talk to anybody she wanted to.” (31-RT2995.) In accord with [Jane Doe 2]’s response, jurors learned that all three complaining communicated with each other for years both digitally and in telephone conversations. (22-RT-1596 and 23-RT-1733-1734 [Jane Doe 3]; 25- RT-2157-2160 [Jane Doe 1]; 28-RT- 2623-2625; 29-RT-2708-2709 [Jane Doe 2].)

G. Jury Deliberations.

There was no dispute that the critical question for the jury involved determining whether [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2] were credible. The state’s position, of course, was the witnesses were credible. The defense position, based in part on the shifting nature of the stories they presented, was that they should not be believed. At both the first and second trials, the jury wrestled with this question.

As noted above, the first jury deliberated for six days, before hanging 10-2 for acquittal as to [Jane Doe 1], 8-4 for acquittal as to [Jane Doe 2] and 7-5 for acquittal as to [Jane Doe 3]. (11-CT-3048-3049, 3054; 8-RT-504.) The second jury also struggled, deliberating all day on May 17 and May 18, returning with one question for the court. (11-CT-3288-3289.) Jurors deliberated all day on May 20, returning with two more questions. (11-CT-3290.) One question jurors asked that day went specifically to the defense theory that the witnesses’ communication with each other over many years had contaminated their recollection; jurors asked to see “all social media correspondence, emails, and texts among the three [complaining] witnesses . . . .” (36-RT-3442.) Because the court had denied defense counsel’s specific request to serve subpoenas on the complaining witnesses for this exact information (11-RT-578-579), all the court could do in answering this question from the jury was to advise jurors they would not be receiving this evidence. (36-RT-3442.)

Jurors deliberated all day on May 22, half a day on May 23, and a full day on May 25, returning with a fourth question for the court. (11-CT-3292- 3294.) Jurors deliberated all day on May 26. (11-CT-3296.) On May 31, jurors finally reached verdicts, hanging again as to [Jane Doe 3] and convicting as to [Jane Doe 1] and [Jane Doe 2]. (11-CT-3298-3299; 39-RT-3485-3489.)

ARGUMENT

ERRORS REQUIRING REVERSAL OF BOTH COUNTS

I. PROSECUTION IN THIS CASE WAS BARRED BY THE TEN-YEAR STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS APPLICABLE TO THE CHARGED OFFENSES.

A. Introduction.

The June 16, 2020 felony complaint filed charged appellant with three separate counts of forcible rape in violation of § 261(a)(2), alleged between 2001 and 2003. (1-CT-76-80.) The subsequent information accurately noted that each offense carried a potential prison term of 3, 6 or 8 years in state prison. (2-CT-344.)

Typically, the particular statute of limitation applicable to an offense depends on the punishment prescribed for that offense — the general rule is that the more serious the punishment, the longer the statute of limitations. Because many California offenses prescribe lower, middle and upper terms for a conviction, Penal Code § 805 — enacted in 1984 — provides that “for purposes of determining the applicable” statute of limitations “[a]n offense is deemed punishable by the maximum punishment prescribed by statute for the offense, regardless of the punishment actually sought or imposed.” (Penal Code § 805(a).)

At the time of the offenses alleged in this case (2001 to 2003), Penal Code § 800 provided that when an “offense [is] punishable by imprisonment . . . for eight years or more” the statute of limitations is “six years after commission of the offense.” Under this provision, because the maximum sentence for forcible rape was 8 years, the applicable statute of limitations was six years.

But at the time of the charged offenses, a person convicted of violating § 261 was required to register as a sex offender pursuant to Penal Code § 290(a). As such, at the time of the charged offenses, the statute of limitations for these crimes was actually 10 years. (See Pen. Code, former § 803, now codified at § 801.1(b) [providing a 10-year limitations period for offenses requiring registration].) Because the felony complaint here was not filed until 2020, and the charged crimes occurred between 2001 and 2003, prosecution was barred by this 10-year statute of limitations.

At trial, the state proposed a different analysis, relying on the interplay between § 805 and Penal Code § 799. (1-CT-31-36.) Section 799 provides in relevant part that there is no statute of limitations for “an offense punishable by . . . imprisonment in the state prison for life . . . .” (1-CT-34.) And as noted above, the first sentence of § 805(a) provides that in determining the applicable statute of limitation “[a]n offense is deemed punishable by the maximum punishment prescribed by statute for the offense . . . .” Putting two and two together, the state argued (1) although it charged appellant with forcible rape (punishable by a maximum term of 8 years in prison), it had added an allegation under § 667.61(e)(4) that multiple victims were involved, (2) in contrast to the 8-year maximum term for a § 261 violation, the § 667.61 multiple victims allegation provided an alternative penalty — 15 years-to-life — for a conviction if multiple victims were involved and (3) because appellant was therefore subject to a life term, pursuant to § 799 there was no statute of limitations. (1-CT-35-36, 58-59.)

On its face, of course, this was a perfectly logical argument. The problem arises from the second sentence of § 805(a), where the Legislature placed an important limitation on the principle that “[a]n offense is deemed punishable by the maximum punishment prescribed by statute for the offense.” That limitation is clear: in determining the maximum punishment, “[a]ny enhancement of punishment prescribed by statute shall be disregarded.”

At trial, the state’s position was this. In light of § 805, the state conceded that “sentence enhancements and prior convictions are generally disregarded in determining the maximum possible punishment for statute of limitations purposes.” (1-CT-36.) In the state’s view, however, the phrase “any enhancement of punishment prescribed by statute” did not include the alternate life-term penalty provided in § 667.61 because “unlike an enhancement, which provides for an additional term of imprisonment, an alternative sentencing scheme sets forth an alternate penalty for the underlying felony itself.” (1-CT-35-36.) Thus, the § 667.61 “life term does not . . . constitute a sentence enhancement because it is not imposed in addition to the sentence for the underlying crime . . . rather, it is an alternate penalty for that offense.” (1-CT-36.) And because “§ 667.61 is an alternate penalty scheme that, when charged, defines the length of imprisonment . . . . the unlimited time frame for prosecution set out in Penal Code § 799 . . . applies.” (1-CT-36.) The court agreed, rejecting appellant’s argument that prosecution was time barred. (1-CT-146-152.)

So the question at the heart of the statute of limitations issue in this case is simple: what did the Legislature intend in § 805 when it used the phrase “any enhancement of punishment prescribed by statute shall be disregarded”? Plainly the Legislature intended to exclude something from the maximum punishment calculus required under § 805. But by using the phrase “any enhancement of punishment” did the 1984 Legislature intend that only some enhancements be disregarded — traditional enhancements where a prison term is added on to a base term? Or did the Legislature also intend to exclude enhancements that come in the form of alternative penalties provided in lieu of a base term?

Appellant concedes that if the Legislature intended that only traditional enhancements be disregarded in determining the maximum punishment for an offense, then the state’s statute of limitations argument is entirely correct, and there was no statute of limitations bar to prosecution here. But by a parity of reasoning, if the Legislature intended that the enhanced punishment provided in alternate penalty schemes also be disregarded, then prosecution was barred in this case. As discussed below, the plain language of the exclusion — “any enhancement of punishment” — is open-ended and all encompassing. The state’s argument that the phrase “any enhancement . . . shall be disregarded” should instead be interpreted to mean that only some enhancements shall be disregarded is untenable in light of § 805’s language, the Law Revision Commission’s Comments to that section setting forth examples of the types of enhancements covered by the exclusion, the location of the statute and — most importantly — by basic canons of statutory construction. Reversal is required.

B. The Legislature’s 1984 Overhaul Of California’s Statute Of Limitations Provisions And Enactment Of §§ 799 And 805.

In 1981, the California Law Revision Commission (“Commission”) was directed to make a study of the statutes of limitation applicable to felonies and to submit to the Legislature recommendations for legislative changes. (See Stats. 1981, Chapter 909, Sec. 3.) At the time, California’s statute of limitations scheme did not (as it does now) largely tie the limitation period applicable to a criminal offense to the punishment prescribed for that offense. Instead, California law set forth limitations periods offense by offense. (See Former Penal Code §§ 799, 800(a)-(c).)

As the Commission noted, prior to 1984, California’s “statute of limitations for felonies has been subject to piecemeal amendment, with no comprehensive examination of the underlying rationale for the period of limitation, nor its continued suitability as applied to specific crimes or categories of crimes.” (17 Reports, Recommendations, And Studies, Recommendation Relating to Statutes of Limitation for Felonies (1984) at p. 307 (“1984 Commission Report”).) The then-current scheme was “complex and filled with inconsistencies”; “the result of fragmentary, ad hoc amendment.” (Id. at pp. 307, 308.) Because this offense-by-offense scheme did not make the limitation period depend on the maximum sentence which could be imposed for any offense, there was no need for the Legislature to address the role of enhancements in determining the appropriate limitations period. Simply put, enhancements had no role at all in the determination of what statute of limitation to apply to an offense.

In January 1984, the Commission submitted recommendations to the Legislature intended to revise the law governing statutes of limitation “on a systematic and comprehensive basis.” (Id. at p. 308.) Current Penal Code §§ 799 through 805 were all part of these recommendations. These changes reflect the Legislature’s decision to switch from a “fragmentary, ad hoc” scheme with no underlying rationale to one which assigned limitations periods based on the seriousness of that crime as measured by the statutory punishment authorized for the crime itself. As recommended by the Commission, (1) § 799 provided there would be no statute of limitation for offenses punishable by death, life without parole or life and (2) § 805 provided that an offense was “deemed punishable by the maximum punishment prescribed by statute for the offense.” (Id. at p. 318, 323.)

In contrast to the pre-1984 “offense-by-offense” approach to statutes of limitation, the new focus on the “maximum punishment prescribed” as the touchstone in determining the applicable limitations period meant that for the first time, the Legislature would now have to address the impact of potential enhancements on the statute of limitations. The Legislature did so in § 805, continuing this approach, providing that “[a]ny enhancement of punishment prescribed by statute shall be disregarded in determining the maximum punishment prescribed by statute of an offense.” (Id. at p. 323.) The Commission included a comment to § 805, giving examples of the types of enhancements to be disregarded in assessing the maximum term of punishment, providing that “[t]he punishment for an offense is determined without regard to enhancements over the base term for the purpose of determining the relevant statute of limitations. See, e.g., §§ 666-668.”

C. The Plain Language Of § 805 Requiring “Any Enhancement Of Punishment” To Be Disregarded In Calculating Statutes Of Limitation Precludes Using The § 667.61 Multiple-Victims Life Term In Determining The Statute Of Limitations.

In determining the intent behind a statute, courts look first to the words of the statute. (DuBois v. Workers' Comp. Appeals Bd. (1993) 5 Cal.4th 382, 387.) Here, § 805 provides “[a]ny enhancement of punishment prescribed by statute shall be disregarded in determining the maximum punishment prescribed by statute of an offense.” (Emphasis added.)

The term “any” when used in a statute has a long history in California. As our Supreme Court has recognized, “[f]rom the earliest days of statehood we have interpreted ‘any’ to be broad, general and all embracing.” (California State Auto. Assn. Inter-Ins. Bureau v. Warwick (1976) 17 Cal.3d 190, 195. Accord Davidson v. Dallas (1857) 8 Cal. 227, 239.) “The term ‘any’ (particularly in a statute) means ‘all’ or ‘every.’” (Droeger v. Friedman, Sloan & Ross (1991) 54 Cal.3d 26, 38.) In light of this longstanding definition of the term “any,” there are three fundamental principles of statutory construction which compel a conclusion that the allinclusive term “any enhancement” in § 805 means just what it says.

First, the Legislature is presumed to have been aware of existing case law when it enacted § 805. (People v. Harrison (1989) 48 Cal.3d 321, 329; People v. Hernandez (1988) 46 Cal.3d 194, 201.) Thus, the Legislature is presumed to have been aware of the “broad, general and all embracing” judicial interpretations of the word “any.”

Second, “where the Legislature uses terms already judicially construed, the presumption is almost irresistible that it used them in the precise and technical sense which had been placed upon them by the courts.” (People v. Hurtado (2002) 28 Cal.4th 1179, 1188. Accord Richardson v. Superior Court (2008) 43 Cal.4th 1040, 1050; People v. Lawrence (2000) 24 Cal.4th 219, 231; People v. Tufunga (1999) 21 Cal.4th 935, 947.) Thus, by using the term “any enhancement” to describe the prison terms that “shall be disregarded in determining the maximum punishment,” the presumption “is almost irresistible” that the Legislature used this word “in the precise and technical sense which had been placed upon [it] by the courts.” In other words, the Legislature intended it to mean that “all or every” enhancement[s] should be disregarded. (Droeger, supra, 54 Cal.3d at p. 38.)