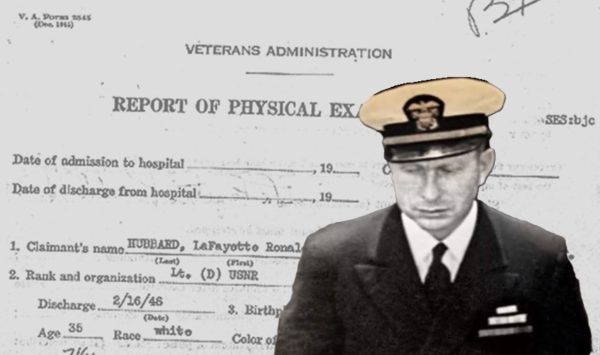

On Veterans Day 2021, Scientology once again showed that its spokespeople continue to lie about L. Ron Hubbard’s questionable war record. As the Bunker reported that year, Clearwater, Florida Scientology spokesperson Pat Harney put out a press release to mark Scientology’s involvement in a Veterans Day event in Clearwater. She claimed that Hubbard – a US Navy lieutenant during World War II – suffered “life-threatening injuries” during his service.

It’s remarkable that Scientology was still claiming this, 35 years after it was first exposed as a lie. We’ve covered the truth before, so we turned to Chris Owen, author of “Ron the War Hero” — the definitive account of Hubbard’s wartime career — to explain why Scientology still makes this debunked claim. Why does Scientology still claim Hubbard was seriously wounded during the Second World War? As Chris explained, it had no real choice. It wasn’t just another of Hubbard’s many tall stories. It was a claim that is foundational to Scientology and has been required reading for every Scientologist for the past 59 years. And now, for Veterans Day 2024, we are proud to publish Chris’s excellent response once again.

The claim comes from Hubbard’s January 1965 essay, “My Philosophy,” in which he wrote:

Blinded with injured optic nerves, and lame with physical injuries to hip and back, at the end of World War II, I faced an almost non-existent future. My service record states: “This officer has no neurotic or psychotic tendencies of any kind whatsoever,” but it also states “permanently disabled physically.”

And so there came a further blow – I was abandoned by family and friends as a supposedly hopeless cripple and a probable burden upon them for the rest of my days. Yet I worked my way back to fitness and strength in less than two years, using only what I knew about Man and his relationship to the universe … Yet I came to see again and walk again.

“My Philosophy” is not just another of the many thousands of hastily written memos and articles that Hubbard penned during his 34-year career as Scientology’s founder and leader. The essay is his most iconic justification for Scientology’s existence. It’s displayed prominently in Scientology orgs, on Scientology websites, and even in a glossy video.

Oddly enough, before writing “My Philosophy” Hubbard was much less extravagant in claiming war wounds. He told Scientologists in a 1958 interview that when he was at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital he “wasn’t sick, I was just banged up.” In an early 1960s interview he stated that he had spent “the last year of my naval career in a naval hospital. Not very ill, but I had a couple of holes in me – they wouldn’t heal. So they just kept me.”

So was Hubbard ever ‘crippled and blinded’? Scientology certainly thinks so: it says that his claim “is referencing wounds sustained in combat on the island of Java and aboard a corvette in the North Atlantic.” However, there is no record of Hubbard having been anywhere near Java, nor of having served aboard a corvette in any ocean, nor sustaining any wounds in combat at any time (or indeed ever seeing combat in the first place).

Instead, his Active Duty Fitness Reports – which cover a period from March 1941 to his final active service assessment on December 6, 1945 – show a range of fairly minor if annoying ailments. These included deteriorating eyesight, conjunctivitis, haemorrhoids, urethral discharges (likely caused by a sexually transmitted disease), arthritis, and a duodenal ulcer for which he was treated at Oak Knoll.

They do not record any combat injuries, which is hardly surprising given that none of the vessels he served on engaged in combat during his time on board. Most notably, there is no sign that Hubbard himself ever claimed to the Navy that he had suffered combat injuries. His own list of ailments comprised:

Malaria, Feb 42, Recurrent;

Left Knee, Sprain, March 1942;

Conjunctivitis, Actinic Mar 42 (eyesight Failing)

Sporad. Pain Left side and back, undiagnosed, July 42;

Ulcer Duodenum, Chronic, Spring 43;

Arthritis, Rt Hip, Shoulder, Jan 45.

The Veterans Administration rated Hubbard only 10 percent disabled when he was discharged in December 1945. Hubbard appealed, claiming that his sore eyes meant that “I can’t read very much and I have severe headaches which radiate backwards. This handicaps me in my research work when I’m working on my writings.” His stomach trouble limited his diet, and his bad hip meant that he “can’t sit any length of time (at typewriter or desk) and restricts me to warm climates.”

Did Hubbard believe his own claims? There certainly seems to have been something going on with his health. Measurements of his eyesight show a marked deterioration during his active service, though his eyes were far from perfect at the start. As early as 1929, his eyesight was rated too poor for him to pass the Navy fitness examination, though this was discounted due to an urgent need for manpower when he joined the Service in 1941. He claimed to have fallen off a ladder on a ship in mid-1942, which could well have accounted for his sporadic back and side pain, and medical examinations confirmed the existence of an ulcer. Some of his other claimed ailments were more dubious. Although arthritis was diagnosed at one point, an August 1951 medical examination found no clinical evidence of it.

In his so-called ‘Affirmations’, written around 1946 or 1947, Hubbard affirmed various positive mental and physical states in an apparent effort to boost himself through positive thinking:

Your ulcers are all well and never bother you. You can eat anything.

You have a sound hip. It never hurts.

Your shoulder never hurts.

Your sinus trouble is nothing.

The [foot] injury is no longer needed. It is well. You have perfect and lovely feet.

When you tell people you are ill, it has no effect upon your health. And in Veterans Administration examinations you’ll tell them how sick you are; you’ll look sick when you take it; you’ll return to health one hour after the examination and laugh at them.

No matter what lies you may tell others, they have no physical effect on you of any kind. You never injured your health by saying it is bad. You cannot lie to yourself.

His statements suggest that he genuinely believed that he had painful physical ailments and wanted to minimize their effects, while at the same time exaggerating them for the benefit of VA doctors in his quest for a bigger disability pension.

His biggest problem, however, was likely psychological. In October 1947, he wrote to the VA requesting that he be “treated psychiatrically or even by a psychoanalyst” after suffering ”long periods of moroseness and suicidal inclinations,” which caused him to try and fail “for two years to regain my equilibrium in civil life.”

He struggled to resume his pre-war writing career after leaving the Navy in December 1945 and only sold a handful of pieces to magazines between 1946 and 1948. Whatever authorial spark had sustained him in the 1930s, it had clearly deserted him by the time the war was over. His apparent hypochondria never left him – in the 1960s and 1970s he tormented his Sea Org ‘Messengers’ with obsessive demands for spotless surroundings and scent-free clothes.

Hubbard’s salvation was his development of Dianetics in 1949-50, which earned him a short-lived fortune. However, although Dianetics and early Scientology were explicitly marketed by Hubbard and others as delivering cures even for serious conditions such as cancer, he did not make exaggerated claims about sustaining war wounds.

In Look magazine’s December 5, 1950 issue, he said that had suffered from “ulcers, conjunctivitis, deteriorating eyesight, bursitis and something wrong with my feet,” which matches well with his Naval medical record. Similarly, in a 1952 lecture, he said that his disability was “arthritis and ulcers and a couple of other minor things”, which he claimed Dianetics had “knocked out” and had resulted in the loss of his “naval retirement”. He made no claims of having suffered “grievous wounds” when he was examined by VA doctors in August 1951.

It was not until January 1965 that Hubbard began making prominent public claims that he had been severely wounded during the war. What could have prompted such a change?

A factor that I think has been underestimated by many of Hubbard’s biographers over the years has been the extent to which he was driven by, in Prof. Stephen A. Kent’s evocative phrase, “malignant narcissism.” I’ve come to appreciate in the course of writing a new book on Hubbard’s life how much his actions were driven by knee-jerk responses to short-term challenges or crises. Consequential events in Scientology’s history can often be linked to individual events, and even individual media articles. As the American Psychiatric Association puts it, a malignant narcissist “may react with disdain, rage, or defiant counterattack” to events that bruise their ego.

The writing of “My Philosophy” seems to fall into this category. At the time, Scientology was facing the worst crisis in its history – the Board of Inquiry set up by the Australian state of Victoria, under the chairmanship of Kevin V. Anderson, QC. Scientology had already experienced years of frequently lacerating criticism in the Australian press. Bad publicity and public complaints had led inexorably to political pressure for a public inquiry into Scientology.

The result was Anderson’s inquiry, which savagely condemned every aspect of Scientology when its very comprehensive report was published in October 1965. The report led to bans on Scientology in three Australian states and, indirectly, to the imposition in the UK of restrictions on Scientology and a visa ban on Hubbard himself in 1967.

The storm had not yet hit Scientology when Hubbard wrote “My Philosophy.” On December 14, 1964, the Anderson Inquiry finished the hearing of formal evidence. It had sat for 160 days and heard evidence from 151 witnesses, including leading Australian Scientologists. Hubbard, though, refused to appear. At the start of December he ordered his representatives to end cooperation with the inquiry, complaining that the inquiry had become a ‘witchhunt.’

Hubbard appears to have planned to travel to Australia in early 1965 but decided not to do so, probably for fear that he would be subpoenaed by the inquiry. Anderson indicated in December 1964 that he would “consider a final address being made to [the Board] by a responsible person respecting scientology interests,” to go alongside the Board’s own final address in February 1965.

“My Philosophy” was published in January 1965, a few weeks after the end of the inquiry’s public phase. It is possible that Hubbard intended it to be Scientology’s final address to the Board of Inquiry, though it does not seem to have been used as such. The entire 1,209-word essay was clearly meant to be an extended apologia for Scientology and for Hubbard himself. Both had come under harsh public criticism, and the essay alludes to the hostility that Scientology faced.

Hubbard tried to delegitimize his critics by claiming that Scientology was opposed by “the slave master” and “bigoted men,” and was “not very popular with those who depend upon the slavery of others for their living or power.” “[O]ne should keep going despite heavy weather for there is always a calm ahead,” Hubbard wrote optimistically, as “the old must give way to the new, falsehood must become exposed by truth, and truth, though fought, always in the end prevails.”

Nearly half of “My Philosophy” deals with Hubbard’s claims about his own life story. It ranges from his much-exaggerated childhood wanderings in Asia (in reality, teenage tourist trips with his parents) to his wartime career and his subsequent development of what became Scientology. It was in this context that he introduced the claim that he had been “blinded” and “lame[d]” with crippling permanent disabilities.

Hubbard had good reason to exaggerate his own significance. He had been particularly harshly criticized a few months earlier by Dr. Cunningham Dax, the director of Victoria’s Mental Health Authority, who told the Inquiry that Hubbard’s writings showed evidence of the writer being mentally ill. Dax claimed that some of Hubbard’s comments “could only have been written by a person emotionally disturbed, and in some passages highly sadistic.” Documents seen by the Inquiry highlighted Hubbard’s role in ordering Australian critics of Scientology to be investigated by private detectives. Not surprisingly, the Inquiry’s final report was very uncomplimentary about him.

Hubbard’s preemptive response was to present himself as a person of extraordinary experience who had done extraordinary things. It was no longer sufficient to present himself as merely the victim of “arthritis and ulcers”; now he had to be a fully-fledged war hero who had nearly made the ultimate sacrifice for his country. He also had to defend himself from charges of being a mentally unbalanced quack, which he did by presenting himself as a selfless philosopher who had dedicated his life to helping and healing others – starting with himself.

“My Philosophy” never served its likely intended role of countering the Inquiry’s February 1965 summing-up, but it came to serve a much more important role for Scientology. It provides ready answers for Scientologists to the many criticisms which Scientology and Hubbard have attracted over the years. The essay portrays Hubbard as a good and wise man who had sacrificed much to help others and Scientology as a force for good in the world.

Hubbard’s claims have obvious parallels with the story of Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection, though it’s hard to say whether he himself ever made this connection. Hubbard’s supposed war wounds were his own personal Calvary: he sacrificed his health for others, just as Jesus submitted to crucifixion, and through his own personal qualities he redeemed himself, just as Jesus’s divine nature led to the resurrection. Jesus had died and was resurrected to atone for mankind’s sins; two thousand years later, Hubbard had found a way to recover from his war wounds and find a new path for mankind. Now, he wrote in “My Philosophy”, Scientology could “show Man how he can set himself or herself free.”

So it’s no wonder that Scientology cannot break away from Hubbard’s claims to have sustained war wounds. In its own way, it’s as foundational as the Crucifixion and Resurrection are to Christianity. This point did not escape Scientology’s former principal spokesperson, Tommy Davis, when he was challenged on Hubbard’s war record in an interview. If it was true that Hubbard had not been injured, he admitted, “the injuries that he handled by the use of Dianetics procedures were never handled, because they were injuries that never existed; therefore, Dianetics is based on a lie; therefore, Scientology is based on a lie.”

— Chris Owen

Want to help?

Please consider joining the Underground Bunker as a paid subscriber. Your $7 a month will go a long way to helping this news project stay independent, and you’ll get access to our special material for subscribers. Or, you can support the Underground Bunker with a Paypal contribution to bunkerfund@tonyortega.org, an account administered by the Bunker’s attorney, Scott Pilutik. And by request, this is our Venmo link, and for Zelle, please use (tonyo94 AT gmail). E-mail tips to tonyo94@gmail.com.

Thank you for reading today’s story here at Substack. For the full picture of what’s happening today in the world of Scientology, please join the conversation at tonyortega.org, where we’ve been reporting daily on David Miscavige’s cabal since 2012. There you’ll find additional stories, and our popular regular daily features:

Source Code: Actual things founder L. Ron Hubbard said on this date in history

Avast, Ye Mateys: Snapshots from Scientology’s years at sea

Overheard in the Freezone: Indie Hubbardism, one thought at a time

Past is Prologue: From this week in history at alt.religion.scientology

Random Howdy: Your daily dose of the Captain

Here’s the link to today’s post at tonyortega.org

And whatever you do, subscribe to this Substack so you get our breaking stories and daily features right to your email inbox every morning.

Paid subscribers get access to a special podcast series…

Group Therapy: Our round table of rowdy regulars on the week’s news

I believed Hubbard. I was with him on his ship in 1974. In essence he never left the Navy because formed his own called the Sea Org. He seemed most at home with naval cap and cape. He was completely in his element as the commodore, ruler over his minions. He was such a convincing liar.

A teller of tall stories. A fiction writer.

Chris Owen nails the lying bastard to the wall. The Hubster started his 'war wounds' crap while he was at Princeton doing some Navy course in civilian administration. While there, he spent a lot of time with Robert Heinlein at the Philadelphia Navy Yard where Heinlein was doing some work. Heinlein asked his group of sci-fi writers to give Hubbard some 'room' as he was a wounded Navy man, hurt during a torpedo attack somewhere.

I am surprised that Hubbard's injuries from a Japanese machine gun weren't claimed until '65. All of the official injuries the Hubster 'suffered' amount to mostly stress related causes. As for the ulcer, no one in 1945 knew about Helicobacter and its role in ulcers.