With the disturbing allegations against Neil Gaiman blowing up after a New York magazine cover story this week, other publications have been scrambling to cover the controversy and have also offered up some stories about Gaiman’s Scientology past.

That’s a subject we’ve been covering for quite a few years, which is why Tortoise Media interviewed us for their podcast which first broke the allegations of several women about Gaiman last summer.

We were glad to help out those journalists, and New York’s Lila Shapiro, as they wondered about Gaiman’s upbringing and his later behavior towards numerous women.

Both the podcast and Shapiro’s cover story covered Gaiman’s Scientology past briefly. But we’ve noticed that people are interested in more information about it, and they’ve been digging up a lengthy piece we posted at our dot org site in 2013, when Gaiman’s novel The Ocean at the End of the Lane had come out.

We decided to bring that information over here to our ad-free Substack (which will make it a little easier to read), and to add some updates.

Gaiman’s Scientology background really is interesting, and we’re sure there will be an ongoing debate about how much it has to do with his later behavior with several women. We have cautioned writers about concluding that Gaiman’s being raised in Scientology somehow explains why he’s turned out to be such a creep. We’ve talked to hundreds of former Scientologists who are really terrific people and do not seem to have Gaiman’s issues.

But let’s once again take a look at how Neil was raised in a household infused with the “technology” of L. Ron Hubbard, and wonder about how he turned out.

…….

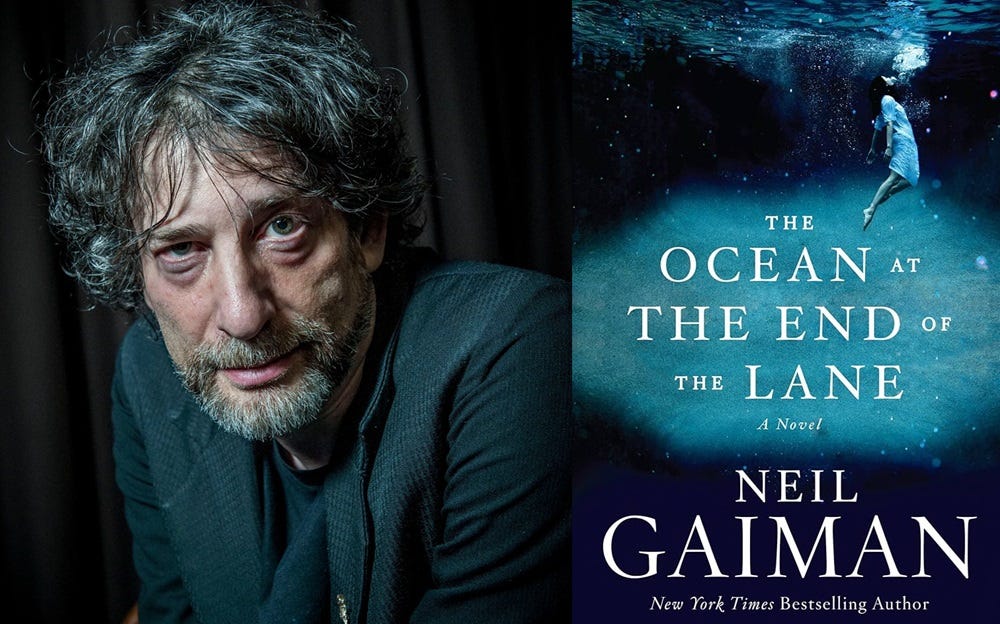

Neil Gaiman’s 2013 book The Ocean at the End of the Lane garnered good reviews and a lot of attention as his first novel for adults in eight years. Gaiman, then 52, was well known for his fantasy and science fiction, including The Sandman comic series, the Hugo-winning novel American Gods, the Hugo-winning novella Coraline, and much more.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a mesmerizing read. We were charmed by its tale of childhood danger and myth stemming from a mysterious suicide on a country lane.

But there’s also a lot here to consider for Scientology watchers. As Gaiman has said in press interviews, his idea for the book came from an actual suicide of a lodger staying in his family’s home a short distance from Scientology’s UK headquarters, where Neil’s father was a prominent executive. And now that we’ve read it, we can say there’s a lot more about Neil’s Scientology past that makes this an interesting read.

Gaiman has called the suggestion that he’s still involved with the Church of Scientology “bonkers”, and we tend to believe him. If he hasn’t criticized Scientology or even really spoken much at all about leaving it behind, it’s not hard to understand why, with his two sisters still in the church, as well as his first ex-wife, whom he still remains friends with. If he were to say a harsh word about the church, Gaiman might find himself completely cut off from his family members still in Scientology, a consequence of the church’s toxic “disconnection” policy.

But if Gaiman has generally avoided the subject, with this book — which he has called his “most personal, ever” — he had to know that he would face questions about his upbringing, his father, and L. Ron Hubbard. And after reading it, we think that’s actually what Gaiman had in mind.

…….

The book begins with a dedication to Gaiman’s second (and now ex-) wife, former Dresden Dolls musician Amanda Palmer: “For Amanda, who wanted to know”

That dedication certainly should have resonance for our readers. Before we explain why, here’s how Gaiman himself explained the genesis of this book in a BBC interview this week:

GAIMAN: It’s absolutely not autobiographical in the sense that it happened to me…And it’s not autobiographical in the sense that the family is not my family. But it’s very, very close to my point of view. I wrote the book because my wife, Amanda, was making a record. She was in Melbourne, Australia, for four months working on a record. And I missed her. So I wrote what started out as a short story for her and then just didn’t stop. And what I had in mind when I wanted to write the short story was something that told her what I was like when I was seven, what it was like to look at the world through my eyes. And also what the landscape that I grew up in was like because that isn’t really there any more. People have built houses all over it, you can’t go back and see it. So I began describing this thing, using elements of fantasy I had when I was a small kid, using an anecdote that I heard about when I was in my forties, that I discovered that we had a lodger who killed himself using our car at the end of our lane, which I’d never known about. And just that piece of information. I thought, well, what would have happened if I’d have been there, what would have happened if it had had strange reverberations, and created a story out of that.

…

NICK HIGHAM: The landscape of this book is East Sussex, you grew up in East Grinstead. And you lived there because your father worked for the Church of Scientology, which is based there, which begs the question, are you now or have you ever been a Scientologist?

GAIMAN: As a child, I suppose I was as much a Scientologist as I was Jewish, which is to say it was the family religion. Am I now? No.

HIGHAM: When did you, as it were, lose the faith?

GAIMAN: I think, I’m, what am I — I’m a writer. And I think for me what fascinates me most is possibilities, is ideas. Um, so even as a kid, I had so many, there were so many religious backgrounds going on. I was at a high church, Church of England school, and I was a reader of science fiction fantasy, that everything sort of became one glorious — what’s the word — morass, blancmange of belief.

Amanda Palmer was in Melbourne from mid-March in 2012, and Gaiman said she was there for four months, which means she finished up recording her album, Theatre Is Evil, about the time Neil finished writing The Ocean at the End of the Lane, in July 2012.

During that time, however, Palmer managed to make a trip to New York in May 2012, and while she was here she crashed the book party of Kate Bornstein, as we reported at the Village Voice.

At the time, we found it very interesting that Palmer supported Bornstein’s book, which describes serving as Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard’s first mate on the yacht Apollo in the early 1970s. Ultimately, Bornstein soured on Scientology and has lost her daughter and granddaughter to the organization.

We got the distinct impression that Palmer, who had married Gaiman the year before, was intrigued by Bornstein’s tale because it does such a good job explaining the mentality of a Scientologist, and from such an insider. At the time, Palmer must have been trying to understand Gaiman’s own past in the organization.

In that light, the book’s dedication — “For Amanda, who wanted to know” — reads to us as Gaiman’s acknowledgment that his wife wanted to hear about his childhood as a Scientologist, which was at least part of the reason he wrote The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

But does that mean that the book should be read as a history of Neil’s time in the church?

…….

Having read it, we can say that there is no Scientology in the book — as far as an explicit representation of the church and how it operates. However, there are quite a few concepts that mirror the ideas of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, ideas that church members would likely recognize.

In the story, the unnamed narrator’s adventures are fueled by an odd family of three women known as the Hempstocks. Gradually, the narrator comes to realize that Lettie and her mother and her grandmother are magical beings who are as old as the universe itself. This seemed very reminiscent of Scientology’s notion of “thetans” — that we are immortal beings who have lived as long as the universe, but without the help of Scientology we are unable to see our true, immortal nature.

The narrator briefly gets a glimpse of the Hempstocks’ power when he is submerged in Lettie’s “ocean” — the pond behind the Hempstock farm. During that moment of clarity, the narrator feels that he perceives all possible knowledge, but it starts to slip away once he is out of the water. He asks Lettie if that’s how she goes through life, with such a complete awareness of the universe.

“It’s really nothing special, knowing how things work. And you really do have to give it all up if you want to play.”

“To play what?”

“This,” she said. She waved at the house and the sky and the impossible full moon and the skeins and shawls and clusters of bright stars.

When we read that, we couldn’t help thinking of L. Ron Hubbard’s assertion that some quadrillion years ago, all-powerful thetans had got to playing around and had created a “MEST” universe — an actual, tangible place of matter, energy, space, and time, and that’s when all the trouble had started.

Lettie later goes through a traumatic experience that appears to leave her dead, but her mother and grandmother assure the narrator that Lettie will eventually be back, after they put her in her “ocean” and she’s carried away by a wave.

The Hempstocks also tell the narrator that he has often visited them over the years, but then always forgets that he does.

Hubbard told his followers that between lives, after we’ve left one corporeal body and then pick up another one, our memories are erased by intergalactic invader forces occupying our solar system so that our true nature as powerful, immortal beings can be kept from us. These “between-life implants” are forced on us at stations on Venus and Mars; after processing, a freshly implanted thetan is then thrown into the ocean at the Gulf of California and then has to make its way to a new human body. Only through his discoveries, Hubbard said, could these implants be erased so that thetans could remain aware of who they were, lifetime to lifetime.

We found several other passages in the book that reminded us of Scientology’s basic ideas, but it’s just as easy to point out that Gaiman is playing with some pretty standard tropes of fantasy and science fiction.

It would probably be a mistake to say that Gaiman is making any kind of statement — positive or negative — about the church and his background in it.

But the truth is, Gaiman’s grounding in Scientology was extensive, and the period he’s mining for fiction could not have been more significant.

The unnamed narrator in the book is seven years old — in fact, it’s the disastrously poor turnout to his seventh birthday that opens the story. In real life, Gaiman was seven when the suicide happened at the end of the lane of his family estate.

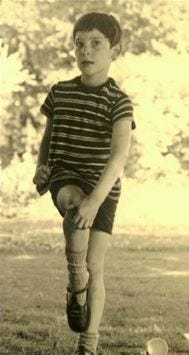

But it was also that same month — August, 1968, that Neil Gaiman’s ardent involvement as a Scientologist became a national issue.

…….

In 1965, David and Sheila Gaiman moved their family to East Grinstead as they became more involved in Scientology, which was headquartered at Saint Hill Manor. L. Ron Hubbard had moved there in 1959 from Washington DC after repeated clashes with American authorities sent him looking for greener pastures.

Gaiman quickly moved up in the organization and was soon doing public relations work. He can be seen briefly in this news report about Scientology’s clash with locals in East Grinstead in 1968. It’s Gaiman who is standing next to Jane Kember, who ran Scientology’s spy wing — the “Guardian’s Office” — for Hubbard and his wife Mary Sue.

As the video indicates, there was a lot of concern about the young people flocking from overseas to Saint Hill Manor to study Scientology. Scientologists knew they weren’t welcome, but they argued back that they were subject to discrimination.

When David’s son Neil was denied entry to a prep school because of his religious affiliation, Gaiman made sure the BBC heard about it.

In 2012, we were the first to post online the transcript from a radio interview of seven-year-old Neil Gaiman, who had been offered to the BBC as the model of a young Scientologist…

Neil Gaiman 7-years-old, Radio Interview BBC Radio ‘World at Weekend’, August 1968.

Keith Graves: What is Scientology?

Neil: It is an applied philosophy dealing with the study of knowledge.Keith Graves: Do you know what philosophy is?

Neil: I used to, but I’ve forgotten.Keith Graves: Who told you that meaning of Scientology?

Neil: In clearer words, it’s a way to make the able person more able.Keith Graves: What does it do for you — Scientology — does it make you feel a better boy?

Neil: Not exactly that, but when you make a release you feel absolutely great.Keith Graves: Do you get what you call a release very often, or do you have this all the time?

Neil: Well, you only keep a release all the time when you get Clear. I’m six courses away from Clear.Keith Graves: You’re on a particular grade are you?

Neil: Well, I’ve just passed Grade I; I’m not Grade II yet.Keith Graves: What is Grade I?

Neil: Problems Release.Keith Graves: And what does this mean to you, Problems Release?

Neil: It helps you to handle quite a lot of problems.Keith Graves: What problems do you have as a little boy that this helps you with?

Neil: Only one big problem.Keith Graves: What’s that?

Neil: My friend Stephen.Keith Graves: Oh, I see. Is he a Scientologist?

Neil: Yes.Keith Graves: But I mean, how does this grade that you’ve got, Problems Release, help you to deal with Stephen?

Neil: Well, you know, I’ve dealed with every single problem except Stephen, one thing Problems Release can’t help me to handle.Keith Graves: So you still fight with Stephen?

Neil: It’s more of a question he fights with me.Keith Graves: He’s older than you, presumably.

Neil: Yes.Keith Graves: And he’s three grades ahead of you?

Neil: In a way, but you see, there are six main courses; but there are ever so many in-between courses. I’ve just finished three, and that’s Engrams.Keith Graves: What are Engrams?

Neil: Engrams are a mental image picture containing pain and unconsciousness.Keith Graves: And what does this mean to you?

Neil: Well, shall I tell you? — I’ll give you a demonstration. You’re walking along the street, and a car hooted and somebody shouted, “shooo’, and a dog barked, and you tripped over a bit of metal and hurt your knee. Three years later, say, you were walking along that same place and someone shouted “shooo”, and a car hooted, and a dog barked, and suddenly you feel pain in your knee. I’ve had one Engram that I can remember. I was jumping off the television set. We’ve got a gigantic television set, but it doesn’t work. Onto my mom’s bed and, you see, I jumped and I hit my head on the chandelier, and you know it really hurt; and I looked up and I saw it swinging, and a few minutes later I tried to test an Engram, so I set it swinging and I looked up there, and I suddenly had a headache.Keith Graves: And how old were you when this happened?

Neil: Around three months ago.Keith Graves: Oh, I see. How long have you been studying Scientology?

Neil: I started at five, now I’m seven.Keith Graves: Seven years old. Extraordinary, isn’t it?

The reason we have this radio transcript was that the church printed up pamphlets intending to sway members of Parliament about Scientology’s supposed persecution. Neil’s interview was just one of several things in that pamphlet. A copy of that pamphlet turned up at a gathering of ex-Scientologists we attended in 2012.

One wonders how much Neil Gaiman today remembers that he was being used in 1968 by Scientology as an example of its beneficial effect on children as a national debate about the church swirled in the press.

…….

What Gaiman says he definitely did not know at the time was that the same month he gave the BBC interview — August 1968 — there was a suicide on his family’s property.

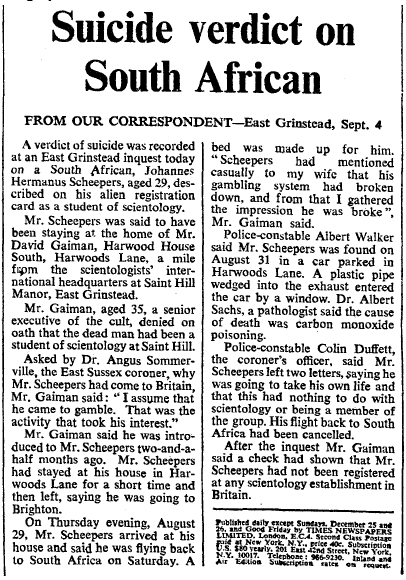

To help make ends meet, the Gaimans took in lodgers among the Scientology students who had come to Saint Hill. And one of them, a 29-year-old South African man named Johannes Hermanus Scheepers, was found dead in the Gaiman family Mini on August 31, 1968. According to an article written at the time, Scheepers had connected a hose from the car’s exhaust to its interior, and had died of carbon monoxide poisoning…

Suicide Verdict on South African

From Our Correspondent — East Grinstead, Sept. 4 [1968]A verdict of suicide was recorded at an East Grinstead inquest today on a South African, Johannes Hermanus Scheepers, aged 29, described on his alien registration card as a student of scientology.

Mr. Scheepers was said to have been staying at the home of Mr. David Gaiman, Harwood House South, Harwoods Lane, a mile from the scientologists’ international headquarters at Saint Hill Manor, East Grinstead.

Mr. Gaiman, aged 35, a senior executive of the cult, denied on oath that the dead man had been student of scientology at Saint Hill.

Asked by Dr. Angus Summerville, the East Sussex coroner, why Mr. Scheepers had come to Britain, Mr. Gaiman said: "I assume that he came to gamble. That was the activity that took his interest."

Mr. Gaiman said he was introduced to Mr. Scheepers two-and-a-half months ago. Mr. Scheepers had stayed at his house in Harwoods Lane for a short time and then left, saying he was going to Brighton.

On Thursday evening, August 29, Mr. Scheepers arrived at his house and said he was flying back to South Africa on Saturday. A bed was wade up for him. "Scheepers had mentioned casually to my wife that his gambling system had broken down, and from that I gathered the impression he was broke", Mr. Gaiman said.

Police-constable Albert Walker said Mr. Scheepers was found on August 31 in a car parked in Harwoods Lane. A plastic pipe wedged into the exhaust entered the car by a window. Dr. Albert Sachs, a pathologist said the cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning.

Police-constable Colin Daffiest, the coroner’s officer, said Mr. Scheepers left two letters, saying he was going to take his own life and that this had nothing to do with scientology or being a member of the group. His flight back to South Africa had been cancelled.

After the inquest Mr. Gaiman said a check had shown that Mr. Scheepers had not been registered at any scientology establishment in Britain.

Even today, David Gaiman’s denials that Scheepers was in any way connected to Scientology seem problematic, as does the notion that Scheepers would have exonerated Scientology in a suicide note and also bothered to cancel his flight home.

In Neil Gaiman’s book, it’s an unnamed opal miner from South Africa who kills himself in the same way after briefly coming to board at the home of the narrator.

The opal miner has left behind two suicide notes (we hear about them from the Hempstocks, who mysteriously seem to know about them), and the notes blame the opal miner’s despair on his bad luck in gambling.

In a strange way, it’s as if Neil Gaiman, in his novel, is providing support for his father’s real-life assertion that the suicide, Scheepers, had died because of gambling, and not because of his involvement with Scientology.

…….

David Gaiman died in 2009 at the age of 75. While he was alive, he was known as a pugnacious promoter of Scientology. He was an unindicted co-conspirator (along with L. Ron Hubbard himself) when 11 Scientology executives were prosecuted for the largest infiltration of the US government in its history. From 1973 until the church was raided by the FBI in 1977, Scientology’s spy wing, the Guardian’s Office, sent operatives to infiltrate hundreds of government offices around the world to pilfer files about the church.

David Gaiman rose to be the Guardian’s Office top public relations official in the world. His own contribution to the GO’s many plots was dreaming up “Operation Cat,” a scheme to plant false information in the files of US government agencies and then expose it using Freedom of Information Act requests. Gaiman’s plans for Operation Cat were among the documents seized in the 1977 raid.

David and his wife Sheila also had a very good thing going after they founded a vitamin supply business, G & G Vitamins, in 1965. It became a lucrative concern as it supplied Saint Hill Manor, where some of Scientology’s processes call for huge intakes of vitamins. (In 2012, Sheila Gaiman was featured in a Scientology flier which listed her as a “New Civilization Founder” in its fundraising for new buildings, indicating that she had personally given at least $1 million.)

But David Gaiman’s career in the church did not go without a hitch. In the early 1980s, there was a purge of old Guardian’s Office executives as Scientology tried to distance itself from the disastrous prosecution of officials involved in Operation Snow White.

In 1983, David was expelled from the church and “declared” a “suppressive person” — Scientology’s form of excommunication. His declare not only lists the usual complaints — that Gaiman supplanted Hubbard’s methods with his own, making him a “squirrel” (a heretic) — but also accused him of “a history of sexual misconduct…He has engaged in this while legally married in disregard of Church policy on this matter.”

David later managed to get back in the church’s good graces, and we have emphasized to journalists who have asked about the document that it’s important to understand that “declares” are notorious for exaggeration — the church describes anyone who is declared as a criminal of the worst sort. And so we think it’s a mistake to read the allegations against David in that document as fully legitimate.

For what it’s worth, in Neil’s novel the narrator’s father is seduced by the evil governess, Ursula Monkton, carrying on an affair while his wife spends evenings in town.

However, as Neil makes clear in the acknowledgments at the end of his book, the family in the novel is not his family in real life. But he also makes an interesting note about how his sister helped him mine the past…

The family in this book is not my own family, who have been gracious in letting me plunder the landscape of my own childhood and watched as I liberally reshaped those places into a story. I’m grateful to them all, especially to my youngest sister, Lizzy, who encouraged me and sent me long-forgotten memory-jogging photographs.

Lizzy Calcioli is an ardent Scientologist who has completed courses up to the present day, according to Scientology’s own publications.

In 2011, the UK’s Channel 4 featured Calcioli in a short film talking about the virtues of Scientology’s silent childbirth. She talked about the noise in other parts of a maternity ward, and how she didn’t want for that to be the “welcome” that her five children experienced.

However, Calcioli never explained in the video why Scientologists seek a silent environment for childbirth: Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard believed that things said while a child is being born would be soaked up by the child’s “reactive mind” and could harm them for the rest of their lives. Hubbard’s book Dianetics is filled with examples of the way a sperm cell, egg, or fetus could absorb things that were said near them while they were “unconscious” and have them manifest as illnesses or neuroses decades later.

Neil Gaiman is also still close with his ex-wife Mary McGrath, whom he met when she was a Scientology student at Saint Hill Manor and lodging in a house owned by Neil’s father. In 1985, they were married and had their first child. (Gaiman and McGrath were divorced in 2008.)

In 2013, when the novel came out, Neil was still living in Minnesota because he wanted to remain close to McGrath and their three children as they were growing up.

As we reported in 2013, Mary McGrath was still so involved in Scientology she had become the executive director of the church’s “Ideal Org” in St. Paul. McGrath has given large donations to Scientology, and some have suggested that Neil is still, through McGrath, giving money to, and is involved in, the church.

But we haven’t seen anything to convince us that Gaiman is involved in the donations made by his ex-wife.

Mary McGrath turned up in a video put together by the St. Paul Ideal Org which encouraged Scientologists from Kansas City to come up to Minnesota for a fundraiser. She shows up with 2:33 on the counter, calling herself “the ED Day”…

As this evidence shows, Neil Gaiman has been surrounded by fanatical Scientologists all of his life, from his father, who spoke for Scientology as its UK mouthpiece, to his sisters, his mother, and his first ex-wife.

But what about Neil himself? We know from the 1968 BBC interview that Neil was raised a Scientologist and by the age of seven could talk confidently about L. Ron Hubbard’s processes. How about years later?

According to Scientology’s own publication The Auditor from August 1978, Neil was declared “Clear” number 6,909. He would have been only 17 at the time. Clear was initially the goal of Scientology processing when Hubbard first developed his movement in the 1950s. By 1978, it had become an intermediate, if still important milestone for an ambitious Scientologist.

In 2023, we got some more confirmation about just how long Neil stayed in the church and continued up its “Bridge to Total Freedom” when Bruce Hines told us about his encounter with him. Bruce is a former very high ranking technical expert and Sea Org member who left Scientology in 2003.

In one of several excellent narratives he’s written for us, Bruce described that in the early 1980s he had been assigned to Scientology’s “Flag Land Base” in Clearwater, Florida, where he gave counseling (“auditing”) to other Scientologists who also had come to the base.

One of those was Neil Gaiman, who would have been in his early 20s. And one thing that stands out in Bruce’s memory, he says, was that he had to use special techniques because Neil was already an OT 3.

“Operating Thetan Level Three” is an advanced achievement in Scientology (well beyond “Clear”) that is notorious because it’s the auditing level when a church member is first let in on the secret story of Xenu the galactic overlord. According to Hubbard, when Scientologists do their past-life therapy and recover memories from ages past, they will eventually remember that 75 million years ago Xenu had committed a bizarre genocide on a planet later known as Earth, and that it was the source of hundreds or thousands of unseen entities that now cling to each person on this planet and can only be removed by years of more expensive auditing.

In other words, Neil Gaiman had not only grown up in Scientology, in his twenties he was still a dedicated and heavily indoctrinated member, so much so that he would travel to Florida for special upper-level processing.

Only a few years later, perhaps by 1985 or so, Neil had left Scientology behind, and turned his attentions to succeeding as a fantasy author.

Then in 2009, he took up with a very different sort of person altogether.

Amanda Palmer rose to fame as one half of the Dresden Dolls and is known for her unconventional cabaret musical style and her unconventional life. In 2012, she became the subject of debate when she used Kickstarter to raise money for a new album that brought in more than a $1 million in donations.

Some Internet posters wondered if any of that money would find its way into the coffers of Scientology, even though there was no evidence that Palmer had any involvement with the church. On May 23, 2012, Palmer answered those critics by posting a photograph of herself topless except for some “Smurf” stickers on her nipples. Written on her torso were the words, “Nope. Not planning to fund Scientology with my Kickstarter money. That would be dumb. P.S., Smurf-tits, AFP [Amanda Fucking Palmer]”

Lila Shapiro’s excellent New York magazine cover story provides much new detail about Gaiman’s relationship with Palmer, the child they had in 2015, and their split in 2015. The article brings up allegations about how much Palmer knew about Gaiman’s troubling involvement with other women. Yesterday, Palmer finally issued a statement about the controversy through one of her representatives.

“While Ms. Palmer is profoundly disturbed by the allegations that Mr. Gaiman has abused several women, at this time her primary concern is, and must remain, the wellbeing of her son and therefore, to guard his privacy, she has no comment on these allegations.”

Gaiman himself issued a much lengthier statement the day before at his own website.

“As I read through this latest collection of accounts, there are moments I half-recognise and moments I don’t, descriptions of things that happened sitting beside things that emphatically did not happen. I’m far from a perfect person, but I have never engaged in non-consensual sexual activity with anyone. Ever.”

He doesn’t mention his Scientology upbringing in the statement, and perhaps it has little to do with the mess that he finds himself in today. But we know that a debate will go on about how much that Neil experienced in such an iconic Scientology family helped to produce the man he later became.

Want to help?

Please consider joining the Underground Bunker as a paid subscriber. Your $7 a month will go a long way to helping this news project stay independent, and you’ll get access to our special material for subscribers. Or, you can support the Underground Bunker with a Paypal contribution to bunkerfund@tonyortega.org, an account administered by the Bunker’s attorney, Scott Pilutik. And by request, this is our Venmo link, and for Zelle, please use (tonyo94 AT gmail). E-mail tips to tonyo94@gmail.com. Find us at Threads: tony.ortega.1044 and Bluesky: @tonyortega.bsky.social

For the full picture of what’s happening today in the world of Scientology, please join the conversation at tonyortega.org, where we’ve been reporting daily on David Miscavige’s cabal since 2012. There you’ll find additional stories, and our popular regular daily features:

Source Code: Actual things founder L. Ron Hubbard said on this date in history

Avast, Ye Mateys: Snapshots from Scientology’s years at sea

Overheard in the Freezone: Indie Hubbardism, one thought at a time

Past is Prologue: From this week in history at alt.religion.scientology

Random Howdy: Your daily dose of the Captain

Here’s the link to today’s post at tonyortega.org

And whatever you do, subscribe to this Substack so you get our breaking stories and daily features right to your email inbox every morning.

Paid subscribers get access to a special podcast series…

Group Therapy: Our round table of rowdy regulars on the week’s news

"but when you make a release you feel absolutely great." Seven year old Neil Gaiman understood the EP of $cientology 'courses' quite well. Selling that 'release' is the auditor's job and someone sold that Piece of Blue Sky to young Neil. Well done Hubbard, you slimy bastard.

Looks like Neil is getting the #metoo treatment. If any of the allegations are true, he deserves every bit of shade that can be thrown at him.

People have choices. They can overcome their past or they can become their past. The hardest thing I have ever done is to quit blaming my past for who I am today. I am in no way perfect. However, I sincerely hope I have broken the chains that forced me to act how I did. If a person continues to use their past as an excuse to misbehave, what good did it do them to leave the past behind?

If the allegations against Neil are true, I sincerely hope they are put in a bright spotlight. It needs to be brought to light that this has been going on for as long as Scientology has existed. The worst of the worst have been sheltered by Scientology. The good ones have been broken or have escaped. This needs to end.