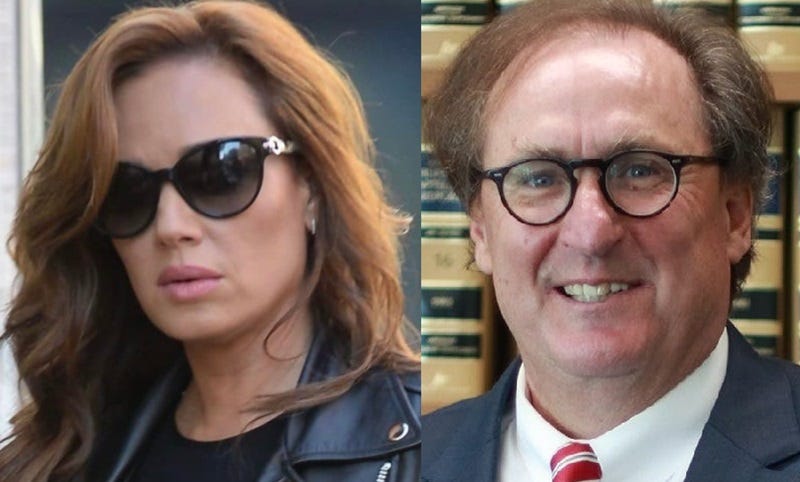

Read the Judge's tentative ruling keeping Leah Remini's suit against Scientology largely intact

Ahead of Tuesday’s hearing, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Randolph Hammock has issued a tentative ruling, granting some of Scientology’s motion to strike portions of Leah Remini’s lawsuit, and sustaining other parts of the lawsuit.

We have been telling you that Leah has been arguing that Scientology’s campaign against her not only defames her but it impacts her ability to make a living, and that it constitutes real harassment and intimidation, not just speech she doesn’t like. Scientology has countered that this is just a free speech fight, and that she is suing for things are not actionable.

You will see that Judge Hammock agrees with the Church that some of the clashes are merely speech fights, but he doesn’t buy Scientology’s excuse that it has been surveilling and investigating Leah since 2013 because she threatened legal action and so Scientology is merely practicing “pre-litigation” research,

That seems like an important ruling by the judge, because even if he has stricken some of Scientology’s smears, the actual conduct by Scientology’s operatives remains something Leah can sue over.

We know this is a lot of legalese, but we figure you’d like to see the whole thing…

Defendants’ Special Motion to Strike is GRANTED IN PART AND DENIED IN PART, as expressly stated infra.

Plaintiff to give notice, unless waived.

DISCUSSION:

Special Motion to Strike

I. Objections to Evidence

A. Plaintiff’s Objections

Plaintiff’s unnumbered objections to the declaration of Lynn R. Farny are OVERRULED. (See generally Sweetwater Union High School Dist. v. Gilbane Building Co. (2019) 6 Cal.5th 931, 947-49 [“evidence may be considered at the anti-SLAPP motion stage if it is reasonably possible the evidence set out in supporting affidavits, declarations or their equivalent will be admissible at trial”].)

On January 3, 2024, Plaintiff filed a “Motion to Strike…” portions of Defendants’ reply, or in the alternative, objections to portions of Defendants’ supplemental declarations filed in support of their reply. (See Plaintiff’s01/03/2024 Filings.) Plaintiff takes issue with the “new evidence.”

“The general rule of motion practice…is that new evidence is not permitted with reply papers . . . . ‘[T]he inclusion of additional evidentiary matter with the reply should only be allowed in the exceptional case’ and if permitted, the other party should be given the opportunity to respond. (Jay v. Mahaffey (2013) 218Cal.App.4th 1522, 1538-1539, quoting Plenger v. Alza Corp. (1992) 11 Cal.App.4th 349, 362, fn. 8.) However, it is permissible to submit reply declarations that “fill[] gaps in the evidence created by the [plaintiff’s]opposition.” (Jay, supra, 218 Cal. App. 4th at 1538.)

This court has reviewed and considered the reply papers and declarations, as well as Plaintiff’s motion to strike and objections to same. It concludes the evidence presented in reply mostly “fill the gaps” in evidence raised in Plaintiff’s opposition. Plaintiff was also given ample opportunity to respond to the evidence in its “motion to strike” and objections. Because consideration of this “new evidence” will not unfairly prejudice Plaintiff, the court exercises its discretion to consider it. [FN 2]

Accordingly, Plaintiff’s 01/03/2024 supplemental objections are OVERRULED.

For the same reasons, Plaintiff’s 01/03/2023 “Motion to Strike, etc.” is DENIED. [FN 3]

B. Defendants’ Objections

Defendants’ objections to the declaration of Linda Singer numbered 1 through 28 are OVERRULED. (See Sweetwater Union High School Dist., supra, 6 Cal.5th at 947-49.)

Defendants’ objections to the declaration of Plaintiff Leah Remini numbered 1 through 144 are OVERRULED. (Id.)

Defendants’ objections to the declaration of Michael Rinder numbered 1 through 46 are OVERRULED. (Id.)

II. Legal Standard

CCP section 425.16 permits the Court to strike causes of action arising from an act in furtherance of the defendant's right of free speech or petition, unless the plaintiff establishes that there is a probability that the plaintiff will prevail on the claim.

“The anti-SLAPP procedures are designed to shield a defendant’s constitutionally protected conduct from the undue burden of frivolous litigation.” (Baral v. Schnitt (2016) 1 Cal.5th 376, 393.) “The anti-SLAPP statute does not insulate defendants from any liability for claims arising from the protected rights of petition or speech. It only provides a procedure for weeding out, at an early stage, meritless claims arising from protected activity.” (Id. at 384.)

“Resolution of an anti-SLAPP motion involves two steps. First, the defendant must establish that the challenged claim arises from activity protected by section 425.16. If the defendant makes the required showing, the burden shifts to the plaintiff to demonstrate the merit of the claim by establishing a probability of success.” (Baral, supra, 1 Cal.5th at 384, citation omitted.) The California Supreme Court has “described this second step as a ‘summary-judgment-like procedure.’ The court does not weigh evidence or resolve conflicting factual claims. Its inquiry is limited to whether the plaintiff has stated a legally sufficient claim and made a prima facie factual showing sufficient to sustain a favorable judgment. It accepts the plaintiff’s evidence as true, and evaluates the defendant’s showing only to determine if it defeats the plaintiff’s claim as a matter of law. ‘[C]laims with the requisite minimal merit may proceed.’” (Id. at 384-385 [citations omitted].) The anti-SLAPP motion need not address what the complaint alleges is an entire cause of action and may seek to strike only those portions which describe protected activity. (Id. at 395-396.)

III. Analysis

A. Background

Parties to the Action

Plaintiff Leah Remini is “a two-time Emmy-award winning producer, actress and New York Times best-selling author.” (Id. ¶ 21.) She starred in the television sitcom “The King of Queens” from 1998 to 2007. (Remini Decl. ¶ 29.)

Defendant David Miscavige is an L.A. resident and the “de facto leader” of the Church of Scientology. (FAC ¶29.) Miscavige “took control” of Scientology in 1986 after the death of its founder, L. Ron Hubbard. (Id. ¶ 36.)Miscavige is responsible for “ensuring the standards, policies, and ethics of Scientology…are carried out.”(Id.)

Defendant Religious Technology Center (“RTC”) is also a California Corporation doing business in Los Angeles, CA. (Id. ¶ 28.) RTC is the “principal management, security, and enforcement entity for Scientology.”(Id.) It “owns, administers and enforces certain IP rights” and “receives licensing fees paid for the use of those rights.” (Id.) RTC also “oversee[s] and direct[s] Defendants’ investigative and policing operations, monitor[s]members’ behavior, and handle[s] matters concerning discipline and punishment.” (Id.) Defendant Miscavige serves as RTC’s “Chairman of the Board,” through which he “control[s] and direct[s] the activities” of the entity Defendants. (Id. ¶ 29.)

Defendant Church of Scientology International (“CSI”) is a California corporation with its primary place of business and headquarters in Los Angeles, California. (Id. ¶ 27.) CSI is the licensee of Scientology’s intellectual Property, who “in turn licenses Scientology’s IP to numerous other Scientology-affiliated entities and organizations.” (Id.) Like RTC, CSI is “controlled and directed” by Defendant Miscavige, “directly and through officers and others who report to him.”

Allegations in the First Amended Complaint

Starting in the 1960s and continuing to this day, Plaintiff alleges the Church of Scientology has “institutionalized a series of retaliatory activities to be taken against any individual, organization, business, or government that Scientology deems to be an enemy.” (Id. ¶ 1.) Under formal Scientology directives, enemies of the church—so-called “Suppressive Persons”—are deemed to be “Fair Game” for retaliation. (Id. ¶¶ 1, 12.)This leaves them vulnerable to “harassment, stalking and other attacks.” (Id. ¶ 56.) One might be become a Suppressive Person by, for example, leaving Scientology, making public statements against it, or consuming media critical of the Church. (Id. ¶¶ 40, 42, 56.) Through various means, the Church and its affiliated entities seek to “obliterate,” “silence,” and “ruin utterly” any individual who is Fair Game. (Id. ¶¶ 16, 43, 47.) No stone goes unturned, and the actions continue until the Suppressive person is “silenced” or “muzzled.” (Id.53.)

Plaintiff alleges she is a “Suppressive Person” who finds herself at the “very top” of Defendant Miscavige’s list of enemies. (FAC ¶ 38) A former Scientologist “of nearly 40 years,” Plaintiff “publicly departed” the Church in 2013 and became an “outspoken public advocate for victims of Scientology.” (Id. ¶¶ 21, 89.)Plaintiff now faces the Church’s alleged “campaign to ruin and destroy [her] life and livelihood.” (Id. ¶ 21.)

The alleged coordinated campaign against Plaintiff is well-documented in the First Amended Complaint. (Id.¶¶ 89-184.) For brevity, the court repeats only some of the allegations here. Plaintiff alleges Defendants have engaged in “a mass coordinated social media effort” to “spread false and malicious information about her through hundreds of Scientology-run websites and social media accounts.” (Id. ¶ 117.) In videotaped messages posted on web addresses using Remini’s name, Defendants “enlisted dozens of current and former Scientologists” to make “disparaging and false claims against” Plaintiff. (Id. ¶ 90.) These included “false and defamatory statements” that Plaintiff is racist, and abusive to her mother and daughter. (Id.) One or more videos include Plaintiff’s estranged and now deceased father, George Remini, who stated she “turned her back” on the family. (Id. ¶ 91.) On Twitter, Defendants allegedly created or run accounts that frequently post “malicious and harassing tweets” about Plaintiff, repeating claims that she supports rapists and abuses her daughter. (Id. ¶¶ 125, 126, 127.)

Defendants’ alleged interference is not just virtual. Plaintiff alleges Defendants have hired investigators to personally stalk and surveil her, causing her to fear for her physical safety. (Id. ¶¶ 106-107, 110, 116.) In one instance, Defendants allegedly retained a security company to install surveillance technology on Plaintiff’s neighbor’s home in order to spy on Plaintiff. (Id. ¶ 110.)

Plaintiff also alleges Defendants undertook efforts to interfere with her “current and prospective business contracts and opportunities.” (Id. ¶ 131.) Defendants made a habit of harassing companies and their advertisers who worked with Plaintiff, including iHeartMedia, AudioBoom, and the Game Show Network. (Id. ¶¶ 132,141, 147.)

The issue is ongoing. Plaintiff alleges continued “aggressive harassment” since the filing of her Complaint in this case. (Id. ¶ 176.) This includes “potential fraud flagged on several of [Plaintiff’s] credit cards,” and surveillance of friends and associates. (Id. ¶¶ 180-182.)

On these allegations and others, Plaintiff brings causes of action against Defendants for (1) Civil Harassment,(2) Stalking, (3) Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress, (4) Tortious Interference with Contractual Relationship, (5) Intentional Interference with Prospective Economic Advantage, (6) Defamation and Defamation Per Se, (7) Defamation by Implication, (8) False Light, and (9) Declaratory Judgment.

B. Prong 1: Defendants’ Protected Activities

Allegedly False Online Statements (FAC ¶¶ 70, 90-91, 103-05, 113-30, 136-38, 148-51, 161-63, 167-68,170-73, 177-78, 227:12-16, 231, 236, 250-51, 263- 65, 273-74, and 283-84)

To satisfy the first prong of the two-prong test, a movant defendant must demonstrate that the act or acts of which the plaintiff complains were taken ‘in furtherance of the defendant’s right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public as defined in the statute. (Equilon Enterprises v. Consumer Cause, Inc. (2002) 29 Cal.4th 53, 67; see City of Cotati v. Cashman (2002)29 Cal.4th 69, 78 [“[i]n the anti-SLAPP context, the critical point is whether the plaintiff's cause of action itself was based on an act in furtherance of the defendant's right of petition or free speech”].)

An “ ‘act in furtherance of a person’s right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue’ includes: (1) any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law, (2)any written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law, (3) any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest, or (4) any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest.” (Code Civ. Proc. § 425.16(e); City of Cotati v. Cashman (2002) 29 Cal. 4th 69, 75 [“section 425.16 expressly ‘defines the types of claims that are subject to the anti-SLAPP procedures’ [citation omitted] i.e., causes of action arising from any act of protected speech or petitioning as these terms are defined in subdivision (e)(1)–(4) of the statute”].)

“[A] claim may be struck [as a SLAPP] only if the speech or petitioning activity itself is the wrong complained of, and not just evidence of liability or a step leading to some different act for which liability is asserted.[Citation].” (Wong v. Wong (2019) 43 Cal. App. 5th 358, 364.) “Thus, in evaluating anti-SLAPP motions, ‘courts should consider the elements of the challenged claim and what actions by the defendant supply those elements and consequently form the basis for liability.” [Citation.] (Id.) The fact “[t]hat a cause of action arguably may have been triggered by protected activity does not entail that it is one arising from such.” (City of Cotati, supra, 29 Cal. 4th at 78 [emphasis added].) It is the “[t]he ‘principal thrust or gravamen’ of the plaintiff's claim [which] determines whether section 425.16 applies. [Citations.]” (Renewable Resources Coalition, Inc. v. Pebble Mines Corp. (2013) 218 Cal.App.4th 384, 394-395.)

Under Baral, this court must consider each category of Defendants’ alleged defamatory statements as a separate “claim” subject to a motion to strike. (See Baral, supra, 1 Cal.5th at 381-382.) This recognizes that in a so-called “mixed cause of action”—one containing allegations of both protected and unprotected activities—a court must focus its analysis on the protected conduct. (Bonni v. St. Joseph Health Sys. (2021) 11 Cal. 5th995, 1010.) It follows that courts may strike improper allegations under the statute even though doing so might not completely dispose of a cause of action.

The moving Defendants first challenge portions of the FAC involving statements allegedly made about Plaintiff by Defendants on social media or in other online forums. (See FAC ¶¶ 70, 90-91, 103-05, 113-30,136- 38, 148-51, 161-63, 167-68, 170-73, 177-78, 227:12-16, 231, 236, 250-51, 263-65, 273-74, and 283-84.)Defendants contend these “claims” qualify under the anti-SLAPP statute as “any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest.”(CCP § 425.16(e)(3).)

“A public forum is a place open to the use of the general public ‘for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions.’” (Weinberg v. Feisel (2003) 110 Cal. App. 4th1122, 1130, [internal citations omitted].) Though public forums traditionally encompassed public spaces like streets and parks, it is well-settled that web sites accessible to the public are also “public forums” for purposes of the anti-SLAPP statute. (Wong v. Jing (2010) 189 Cal. App. 4th 1354, 1366 [collecting cases]; Balla v. Hall(2021) 59 Cal. App. 5th 652, 673 [Facebook posts were made in public forum for anti-SLAPP purposes];Jackson v. Mayweather (2017) 10 Cal. App. 5th 1240 [same]; Packingham v. North Carolina (2017) 137 S. Ct.1730 [recognizing social media as the modern “public forum”].)

Here, the challenged conduct occurred in posts on Twitter (now known as “X”) and other websites operated by Defendants. These forums “hardly could be more public.” (Wilbanks v. Wolk (2004) 121 Cal. App. 4th 883,895.) Plaintiff readily concedes that point.

Defendants go on to argue that the speech in question is an issue of public interest because it “implicates Scientology and Plaintiff’s deliberate years-long attempt to vilify Scientology in the public eye.” (Mtn. 18: 6-7.) Defendants also contend that Plaintiff’s standing as a public figure make the dispute involving her a matter of public interest. Plaintiff sees it differently, arguing the speech is merely “personal attacks” against her, and not protected activity.

“Section 425.16 does not define ‘public interest,’ but its preamble states that its provisions ‘shall be construed broadly’ to safeguard ‘the valid exercise of the constitutional rights of freedom of speech and petition for the redress of grievances.” (Tamkin, supra, 193 Cal. App. 4th at 143 [citing § 425.16, subd. (a)].) “[A]n issue o fpublic interest’ ... is any issue in which the public is interested. In other words, the issue need not be ‘significant’ to be protected by the anti-SLAPP statute—it is enough that it is one in which the public takes an interest.” (Id.) It includes “conduct that could directly affect a large number of people beyond the direct participants” and a “topic of widespread, public interest.” (Balla, supra, 59 Cal. App. 5th at 673.) There must be “some degree of closeness between the challenged statements and the asserted public interest.” (Id.)

In FilmOn.com Inc. v. DoubleVerify Inc. (2019) 7 Cal.5th 133, the Court of Appeal established a two-part inquiry to determine whether a defendant has met its burden to show its alleged wrongful activities fell within the statute’s public interest requirement: “First, we ask what ‘public issue or [ ] issue of public interest’ the speech in question implicates—a question we answer by looking to the content of the speech. [Citation.] Second, we ask what functional relationship exists between the speech and the public conversation about some matter of public interest.” (FilmOn.com, supra, 7 Cal.5th at 149-150.) On the second inquiry, a court must determine if the speech “contributes to—that is, ‘participat[es]’ in or furthers—some public conversation on the issue.” (Id. at 151.) This analysis requires consideration of the particular circumstances in which a statement was made, “including the identity of the speaker, the audience, and the purpose of the speech.” (Id.at 140.)

“FilmOn’s first step is satisfied so long as the challenged speech or conduct, considered in light of its context, may reasonably be understood to implicate a public issue, even if it also implicates a private dispute. Only when an expressive activity, viewed in context, cannot reasonably be understood as implicating a public issue does an anti-SLAPP motion fail at FilmOn’s first step.” (Geiser v. Kuhns (2022) 13 Cal. 5th 1238, 1253–54.)

Here, this court has little trouble concluding that the challenged conduct in this category falls under the public interest. First, at least one Court of Appeal decision held that “a large, powerful organization” like Scientology “may impact the lives of many individuals” and is itself a matter of public interest. (Church of Scientology v. Wollersheim (1996) 42 Cal. App. 4th 628, 650, disapproved of on other grounds by Equilon Enterprises v. Consumer Cause, Inc. (2002) 29 Cal. 4th 53.) There, in a preceding lawsuit, Wollersheim alleged the Church “intentionally and negligently inflicted severe emotional injury on him through certain practices, including ‘auditing,’ ‘disconnect,’ and ‘fair game.’” (Id. at 636.) After Wollersheim obtained a judgment against the Church at trial, the Church filed a new action seeking to set aside the judgment. (Id. at 637-38.) Wollersheim then filed a special motion to strike the complaint. (Id. at 639-640.)

In opposing the special motion to strike, the Church argued its practices were not a public issue. (Id. at 642,650.) The Court disagreed. Although the Church was the plaintiff, the Court reasoned that the Church’s action “ar[ose] from [Wollersheim’s] lawsuit against the Church.” (Id. at 650.) It continued:

The record reflects the fact that the Church is a matter of public interest, as evidenced by media coverage and the extent of the Church's membership and assets. Furthermore, the underlying action concerned a fundamental right, the constitutional protection under the First Amendment religious practices guaranties, and addressed the scope of such protection, concluding that the public has a compelling secular interest in discouraging certain conduct even though it qualifies as a religious expression of the Scientology religion.

Plaintiff’s attempt to distinguish the instant case from Wollersheim falls flat. Plaintiff correctly argues that the analysis of the speech in Wollersheim was somewhat reversed, because the Church was the non-moving party arguing that the challenged speech was not a public issue. But the point holds true.

This court agrees that the public holds a general interest in the Church of Scientology, which includes the Church’s operations and the treatment of members and former members like Plaintiff. As a high-profile organization with past and present celebrity members, the Church has long garnered the interest and imagination of the public at large. (FAC ¶¶ 70, 72, 99.) These stories often play out in a public forum, whether it be on Twitter, television, or in this case—a courtroom.

It is also important to consider that Plaintiff is herself a well-known figure who attracts widespread interest. As already noted, Plaintiff became known for her role in the TV sitcom “The King of Queens” from 1998 to 2007. This notoriety made her the “public face” of Scientology until she “publicly departed” in 2013. (FAC ¶¶ 21,70.)

Since leaving Scientology—and much to the Church’s ire—Plaintiff has actively produced media critical of Scientology. In 2015, Plaintiff released a New York Times bestselling book titled “Troublemaker: Surviving Hollywood and Scientology.” (Id. ¶ 93.) She also produced and hosted the A&E documentary series “Leah Remini: Scientology and the Aftermath.” (Id. ¶ 97.) She now “tirelessly…advocate[s]” for victims of Scientology, and appears on various television shows and podcasts to do so. (Id. ¶ 24.) Through this lawsuit, she seeks to vindicate “others who wish to expose Scientology’s abuses, including journalists and advocates, may feel free to hold Scientology accountable without the fear that they will be threatened into silence.” (Id. ¶25 [emphasis added].)

In other words, this is not a private dispute. When viewed in context, the First Amended Complaint plainly demonstrates that the alleged statements Defendants made about Plaintiff online implicate a broader public dispute over Plaintiff’s relationship with Scientology. And Defendants’ online attack bears more than just a “functional relationship” to that public interest. (FilmOn.com, supra, 7 Cal.5th at pp. 149-150.) The online posts are themselves a part of the public’s interest in Plaintiff and Scientology.

Plaintiff’s arguments to the contrary fall flat. In opposition, Plaintiff relies on a case from the Texas Court of Appeals, Sloat v. Rathbun, 513 S.W.3d 500, 505 (Tex. App. 2015). There, the wife of a former prominent Scientologist brought an action against the Church, alleging a three-year campaign of “ruthlessly aggressive” surveillance, insults, and harassment. (Id. at 504, 505.) The church moved to dismiss the complaint under a Texas state law analogous to the California anti-SLAPP statute, arguing that the action challenged protected activities. (Id. at 505.)

The Court rejected that argument. (Id. at 508.) The Court held the harassing conduct complained of lacked any “direct relationship to” a public interest. (Id.) Importantly, the court reasoned that the plaintiff was neither a public figure nor a limited-purpose public figure. (Id.) Rather, the plaintiff herself “was never a member of the Church of Scientology, did not join her husband in speaking out about Scientology issues, and did not take a public position regarding Scientology.” (Id. at 505.) The record showed the plaintiff had “attempt[ed] earnestly to avoid” the “public controversy” between her husband and the Church. (Id. at 508.) Therefore, the Court concluded that the Scientology defendants failed to meet their burden of demonstrating, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the plaintiff’s claims arose from the exercise of their rights of free speech or association. (Id.at 509.)

Here, unlike in Sloat, Plaintiff herself is a former scientologist who now actively advocates against the Church—often publicly through various mediums. This can hardly be an attempt to “earnestly” avoid the public controversy.

To summarize, the Church is a high-profile entity speaking on a high-profile figure. Plaintiff is a high-profile figure speaking on a high-profile entity. Plaintiff’s speech is at times responsive to, or provoked by, Defendants, and vice versa. By engaging in the back-and-forth, purposely public battle against each other, the parties have made the issue one of significant public interest. (See Jackson v. Mayweather (2017) 10 Cal. App.5th 1240 [action between two “high profile individuals” involving “postings and comments concerning” that relationship were statements in connection with an issue of public interest].)

Therefore, Plaintiff’s allegations concerning Defendants’ online statements about her “arise from” Defendants’ protected activities. Defendants have therefore met their burden for the speech implicated in these portions of the First Amended Complaint. This switches the burden to Plaintiff under the prong two analysis.

Alleged Interference by “Lobbying” Media Outlets and Sponsors. (FAC ¶¶ 95, 97-102, 105, 109, 124,136-38, 142-46, 148-52, 161-63, 167-68, 170-73, 227:12-16, 231, 250-51, 263-65, 269, 273-74, 283-84)

The court now turns to the allegations in the First Amended Complaint detailing Defendants’ alleged interference with Plaintiff’s media relationships. (FAC ¶¶ 95, 97-102, 105, 109, 124, 136-38, 142-46, 148-52,161-63, 167-68, 170-73, 227:12-16, 231, 250-51, 263-65, 269, 273-74, 283-84.)

The claims at issue are as follows: Plaintiff alleges that Defendants sent “disparaging and threatening letters” to ABC News and other media who were promoting Plaintiff’s book. (FAC ¶ 95) She alleges that Defendants organized a barrage of letters sent to media executives in protest of the release of her “The Aftermath” series. (Id. ¶¶ 97-100). Scientologists also sent harassing texts and e-mails to anyone involved in the production of The Aftermath, including family members. (Id. ¶ 101).

Before Plaintiff’s appearance on Conan O’Brien to promote her book, Defendants sent a letter to O’Brien objecting to her appearance and claiming Plaintiff was “speaking out against Scientology for the fame, money and attention.” (Id. ¶ 102). Defendants allegedly sent letters to the President of A&E accusing Plaintiff of inciting the murder of a 24-year-old Taiwanese Scientologist at its Australian Headquarters. (Id. ¶ 105). Finally, in letters to AudioBoom and affiliates, Defendants asserted that advertising on Remini’s podcast would promote religious hate. (Id. ¶¶ 142-46.)

Defendants argue these allegations fall under Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, subdivision (e)(4),which protects other conduct in furtherance of free speech or petition rights in connection with a public issue. (Code Civ. Proc. §425.16(e)(4).) A cause of action arises from protected activity under subdivision (e)(4) if“(1) defendants' acts underlying the cause of action, and on which the cause of action is based, (2) were acts in furtherance of defendants' right of petition or free speech (3) in connection with a public issue.” (Tamkin v. CBS Broad., Inc. (2011) 193 Cal. App. 4th 133, 142–43.) Section (e)(4) is meant to be a broadly construed “catch-all.” (Lieberman v. KCOP Television, Inc. (2003) 110 Cal. App. 4th 156, 164.)

In opposition, Plaintiff contends that Defendants “have failed to meet their burden to show that their harassment of Remini and Remini’s employers and sponsors, and attacks on Remini and her character, are tethered to any issue of public interest.” (Opp. 14: 21-23.) This Court respectfully disagrees.

Here, the analysis discussed in the preceding section largely applies the same. Under FilmOn’s first step inquiry, the “issue of public interest” implicated by the speech at issue is the dispute over Plaintiff’s relationship with Scientology, which necessarily includes Scientology’s alleged campaign to ruin Plaintiff’s career. (FilmOn.com, supra, 7 Cal.5th at 149-50.) The alleged communications were also largely directed to figures with apparent authority over the media productions themselves. The public undoubtedly has an interest in learning about—and discouraging—retaliatory conduct by religious organizations that occurs in a non-secular context.

Second, the “functional relationship” between that speech and the broader public conversation about Scientology is largely one and the same. (Id.) Defendants’ alleged letters and other communications to media figures with control over Plaintiff’s media ventures underly the running dispute between Plaintiff and the Church—a matter which, as has been discussed, the public is interested. The recipients of these letters, by authority or influence, themselves possess power to shape public perception of both Plaintiff and the Church. In that sense, they too contribute to the broader conversation.

Therefore, Plaintiff’s allegations concerning Defendants’ alleged interference with media relationships “arise from” Defendants’ protected activities. Defendants have therefore met their burden for the speech implicated in these portions of the First Amended Complaint. This switches the burden to Plaintiff under the prong two analysis.

Petitioning (Alleged Pre-Litigation Surveillance) (FAC ¶¶ 94, 106, 109-10, 117, 139, 173, 182-83, 227:9,231(a), 236)

Finally, the Court turns to the third category of speech challenged by Defendants, which they deem “pre-litigation surveillance.” Based on their issues with Plaintiff, Defendants contend they were in “a pre-litigation stance” as early as 2013. Any surveillance that followed, Defendants argue, was a pre-litigation investigation in connection with their “right of petition,” and thus also protected under § 425.16, subdivision (e)(4).

Plaintiff alleges she was “followed by private investigators hired by Defendants” in 2015 while in New York to promote her book. (FAC ¶ 94.) In 2017, Defendants allegedly hired investigators from International Investigative Group, Ltd. to surveil and follow her while she was in New York filming. (Id. ¶ 106.) In 2022,Defendants retained a security company to install surveillance technology at Plaintiff’s neighbor’s home, under the guise that Plaintiff herself had sent the company. (Id. ¶ 110.) Defendants directed individuals to follow and harass podcast producers until those producers grew so fearful that iHeartMedia made the decision to terminate the relationship with Plaintiff. (Id. ¶ 139.) Since the filing of the lawsuit, Defendants have also allegedly surveilled Mike Rinder, who co-hosted “The Aftermath.” (Id. ¶ 182.)

Courts have adopted an “expansive view of what constitutes litigation-related activities within the scope of section 425.16.” (Neville v. Chudacoff (2008) 160 Cal. App. 4th 1255, 1268 (2008). Statements made in preparation for litigation or in anticipation of bringing an action fall within the protected categories. (RGCGaslamp, LLC v. Ehmcke Sheet Metal Co. (2020) 56 Cal. App. 5th 413, 425) The parties, however, have not cited case authority applying the first prong of the anti-SLAPP analysis to claims based on surveillance purportedly anticipating litigation.

Defendants cite to the case of Tichinin v. City of Morgan Hill (2009) 177 Cal. App. 4th 1049, to support their argument that their prelitigation surveillance is protected conduct. But the case is mostly inapposite. Tichinin did not address the first prong of the anti-SLAPP analysis. Instead, addressing the merits of a section 1983 claim under the second prong, the Court stated the proposition that “non-petitioning conduct is within the protected ‘breathing space’ of the right of petition if that conduct is (1) incidental or reasonably related to an actual petition or actual litigation or to a claim that could ripen into a petition or litigation and (2) the petition, litigation, or claim is not a sham.” (Id. at 1068.) The issue in the case before us is whether Defendants’ conduct qualifies for protection under the first prong of the anti-SLAPP analysis. Nonetheless, the test adopted in Tichinin may aid that analysis, as discussed further below.

Defendants assert they were in “a pre-litigation stance” at the time of the alleged surveillance. The contemplated litigation arises from Plaintiff’s allegation that Defendants accused her of “filing a false police report and then attempting to extort Scientology.” (FAC ¶ 120.) Defendants do not dispute this. In fact, they provide a copy of an article apparently published by the Church and posted on https://www.leahreminithefacts.org/, which includes the Church’s claim that Plaintiff made a fraudulent “missing person report” on Defendant Miscavige’s wife, Michele Miscavige. (Farny Decl. ¶ 67, Exh. 63; FAC¶¶ 73, 88.) The Church’s article goes on to state that after “inform[ing] the media of Remini’s false report and lack of scruples,” Remini’s attorney “sent the Church back-to-back extortionate demands” for $500,000 and $1million, respectively. (Farny Decl. ¶ 67, Exh. 63.)

Defendants, however, provide no evidence showing when Plaintiff actually made her litigation demands. The implication from their argument is that these demands occurred in 2013, which prompted Defendants to begin surveillance in anticipation of litigation. But Plaintiff’s evidence shows otherwise. In actuality, Plaintiff made her demands—the so-called extortion—in late 2016, after the surveillance had already begun.

This court is mindful that some of the allegations involving surveillance occurred after 2016. (FAC ¶¶ 106,110, 139, 182.) But if Defendants were willing to surveil Plaintiff before the threat of any litigation occurred, they are hard-pressed to demonstrate any protected “pre-litigation” surveillance after the fact.

This is especially true because Defendants provide no evidence—declaration or otherwise—suggesting they reasonably contemplated litigation in good faith at any time. The California Supreme Court has explained that,“[i]n deciding whether the initial ‘arising from’ requirement is met, a court considers ‘the pleadings, and supporting and opposing affidavits stating the facts upon which the liability or defense is based.’ ” (Navellier v.Sletten (2002) 29 Cal.4th 82, 89 [quoting § 425.16, subd. (b)(2), italics added].) This court does not mean to suggest that a moving defendant must always submit evidence in support of prong one. (See Bel Air Internet, LLC v. Morales (2018) 20 Cal. App. 5th 924, 935 [stating “if the complaint itself shows that a claim arises from protected conduct…a moving party may rely on the plaintiff's allegations alone in making the showing necessary under prong one without submitting supporting evidence”].) But here, the protected conduct is not apparent on the face of the FAC. On this record, this court can only conclude that any attempt by Defendants to attribute the surveillance with a good-faith belief in litigation is unsupported by the evidence, and contradicts common sense.

Defendants have submitted a supplemental declaration from Lynn Farny, including an email chain between Mike Rinder and a person identified only as “Laura.” (Farny Supp. Decl. ¶ 8, Exh. 109.) The email chain was produced in discovery in a separate lawsuit. (Id.) In one email dated July 11, 2013, Rinder states that “Leah Remini is looking for a lawyer to possibly represent her against the Church.” (Id.)

This “evidence” creates more questions than answers. It is not clear from this bare line in an email how Rinder knew Plaintiff was looking for a lawyer; what the lawsuit against the Church would be based on; or if the Church had knowledge of a potential lawsuit. This is plainly insufficient to support the Defendants’ burden to establish that the challenged conduct arises from protected activity.

For these reasons, there is an insufficient connection between the alleged surveillance and a public interest. The court sees no public interest in the surveillance of private citizens—even celebrities—under an unsupported suspicion that litigation may occur at some later time. “The fact that ‘a broad and amorphous public interest’ can be connected to a specific dispute is not sufficient to meet the statutory requirements of the anti-SLAPP statute.” (World Financial Group, Inc. v. HBW Ins. & Financial Services, Inc. (2009) 172 Cal.App. 4th 1561, 1570; Rand Resources v. City of Carson (2019) 6 Cal. 5th 610, 625–626 [“At a sufficiently high level of generalization, any conduct can appear rationally related to a broader issue of public importance. What a court scrutinizing the nature of speech in the anti-SLAPP context must focus on is the speech at hand, rather than the prospects that such speech may conceivably have indirect consequences for an issue of public concern.”].) Defendants have therefore failed to meet their burden on this category.

Accordingly, the portions of Plaintiff’s FAC challenged by Defendants in this category, to the extent they are based on allegations of surveillance by Defendants or its agents, fail under prong one. Hence, the analysis of these claims stops here, and the special motion to strike these particular allegations are DENIED.

C. Prong 2: Plaintiff’s Probability of Prevailing on Claims

Merit of Plaintiff’s Defamation-Based Claims (Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Causes of Action)

Having concluded that the claims challenging allegedly false online statements and interference with media outlets or sponsors are subject to anti-SLAPP protection under prong one, this court now turns to the merits of those claims under prong two.

The burden of showing a probability of prevailing on the claims rests with Plaintiff. “To establish a probability of prevailing, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the complaint is both legally sufficient and supported by a sufficient prima facie showing of facts to sustain a favorable judgment if the evidence submitted by the plaintiff is credited. For purposes of this inquiry, the trial court considers the pleadings and evidentiary submissions of both the plaintiff and the defendant; though the court does not weigh the credibility or comparative probative strength of competing evidence, it should grant the motion if, as a matter of law, the defendant’s evidence supporting the motion defeats the plaintiff’s attempt to establish evidentiary support for the claim. In making this assessment it is the court’s responsibility…to accept as true the evidence favorable to the plaintiff […]. The plaintiff need only establish that his or her claim has minimal merit to avoid being stricken as a SLAPP.” (Soukup v. Law Offices of Herbert Hafi f (2006) 39 Cal.4th 260, 291.) As to the second step inquiry, a plaintiff seeking to demonstrate the merit of the claim “may not rely solely on its complaint, even if verified; instead, its proof must be made upon competent admissible evidence.” (Sweetwater Union High Sch. Dist. v. Gilbane Bldg. Co. (2019) 6 Cal. 5th 931, 940.)

Plaintiff brings her Sixth Cause of Action for defamation and defamation per se; her Seventh Cause of Action for defamation by implication; and Eighth Cause of Action for false light.

The elements of a defamation claim are (1) a publication that is (2) false, (3) defamatory, (4) unprivileged, and(5) has a natural tendency to injure or causes special damage.” (J-M Mfg. Co. v. Phillips & Cohen LLP (2016)247 Cal. App. 4th 87, 97.) “A statement is defamatory when it tends ‘directly to injure [a person] in respect to[that person's] office, profession, trade or business, either by imputing to [the person] general disqualification in those respects which the office or other occupation peculiarly requires, or by imputing something with reference to [the person's] office, profession, trade, or business that has a natural tendency to lessen its profits.’(Civ. Code, § 46, subd. 3.)” (McGarry v. University of San Diego (2007) 154 Cal.App.4th 97, 112.)

“In a case in which a plaintiff seeks to maintain an action for defamation by implication, the plaintiff must demonstrate that (1) his or her interpretation of the statement is reasonable; (2) the implication or implications to be drawn convey defamatory facts, not opinions; (3) the challenged implications are not ‘substantially true’; and (4) the identified reasonable implications could also be reasonably deemed defamatory.” (Issa, 31 Cal.App. 5th at 707.)

“False light is a species of invasion of privacy, based on publicity that places a plaintiff before the public in a false light that would be highly offensive to a reasonable person, and where the defendant knew or acted in reckless disregard as to the falsity of the publicized matter and the false light in which the plaintiff would be placed.” (Jackson v. Mayweather (2017) 10 Cal. App. 5th 1240, 1264.)

Defendants argue these defamation-based claims lack even minimal merit because (1) they are time-barred under the statute of limitations, (2) are nonactionable statements of opinion, (3) are nonactionable statements of truth, and (4) were not made with actual malice. The court addresses each of these contentions now.

a. Statute of Limitations

The parties agree that the statute of limitations for defamation is one-year. (CCP § 340(c).) They also agree that period applies to each the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth causes of action.

Defendants argue that Plaintiff’s claims in paragraphs 95, 97-98, 100-105, 109, 116-30, 136-38, 152, 227:12-16, 231, 236, 250-51, and 263-65 all fail, because on the face of the First Amended Complaint, the underlying publications occurred more than one year before August 2, 2023. Defendants also argue those in paragraphs90, 91, 113, 114, 115, and 120 are time barred based on the evidence presented in the Farny Declaration.

Thus, for purposes of this section, the task is to identify if any of these “claims” are conclusively time-barred because they occurred before August 2, 2022, and are not otherwise subject to a recognized tolling exception.

Plaintiff, for her burden, correctly notes there is evidence that posts have been made and published about her on or after August 2, 2022—as is adequately alleged in the FAC, and corroborated in the opposition evidence. Such claims, whether they be on websites or Twitter posts, are timely for purposes of this motion.

Indeed, rather than addressing every challenged claim which may be timely, the court instead focuses its analysis on the ones that plainly are not. Where not otherwise stated, Plaintiff has met her burden to establish prima facie evidence of a timely claim.

Here, the following portions of the FAC are untimely on their face, and Plaintiff has failed to produce prima facie evidence to show otherwise:

(1) Paragraph 95, sending threatening letters to individuals promoting Plaintiff’s 2015 memoir;

(2) at paragraphs 97-98, harassing A&E and collaborators on Plaintiff’s Aftermath series from 2016-2019;

(3) at paragraph 102, a letter to Conan O’Brien criticizing Plaintiff in 2017;

(4) at paragraphs 103 and 104, accusing Plaintiff of inciting Brandon Reisdorf to throw a rock through the Scientology office in 2016;

(5) at paragraph 105, writing letters to the President of A&E accusing Plaintiff of inciting Chih-Jen Yeh’s murder in 2019;

(6) at paragraph 136 and 137, the article published on March 4, 2022; and

(7) at paragraph 152, sending fake journalists to the set of “People Puzzler.”

Second, regarding the allegations in paragraphs 90 and 91, Defendants present evidence that the Scientology videos were first posted online in February 2022. (Farny Decl. ¶ 71.) In addition, the articles and videos referred to at paragraph 115 of the FAC (and apparently referred to at paragraphs 113-114 of the FAC) were made available at Freedommag.org between September 2017 and February 2022. (Id.) Plaintiff does not dispute Defendants’ evidence showing that the statements in paragraphs 90-91 and 113-115 also occurred outside the limitations period. Therefore, these paragraphs are also barred.

At paragraph 120, Plaintiff accuses Defendants of filing a false police report and then attempting to extort Scientology. (FAC ¶ 120.) This seemingly references a February 21, 2022, article posted onhttps://www.leahreminithefacts.org/, which includes the Church’s claim that Plaintiff made a fraudulent “missing person report” on Defendant Miscavige’s wife. (Farny Decl. ¶ 67, Exh. 63; FAC ¶¶ 73, 88.) The Church’s article goes on to state that after “inform[ing] the media of Remini’s false report and lack of scruples,” Remini’s attorney “sent the Church back-to-back extortionate demands” for $500,000 and $1million, respectively. (Farny Decl. ¶ 67, Exh. 63.) Another article accusing Plaintiff of extortion was published on December 2, 2016, on https://www.leahreminiaftermath.com/ titled, “’Leah Remini Aftermath’ is really ‘Leah Remini: After Money.’” (Farny Decl. ¶ 70, Exh. 66.)

As demonstrated, Defendants published each of these articles more than one year prior to the date Plaintiff filed this lawsuit. Under a one-year statute of limitations, they cannot form the basis of her claims.

Accordingly, to the extent they form part of Plaintiff’s Sixth, Seventh, or Eighth causes of action, the following paragraphs or portions of the First Amended Complaint are ordered stricken based on the statute of limitations: paragraphs 90, 91, 95, 97-98, 102, 103, 104, 105, 113, 114, 115, 120, 136, 137, and 152. [FN 4]

b. Statements of Opinion and True Statements

Next, Defendants argue that many of the allegations purportedly giving rise to Plaintiff’s defamation causes of action are either unactionable statements of opinion or truths. This Court agrees with this particular argument to some degree, as noted below.

Because an actionable statement for defamation must contain a provable falsehood, “courts distinguish between statements of fact and statements of opinion for purposes of defamation liability. Although statements of fact may be actionable as libel, statements of opinion are constitutionally protected.” (Summit Bank v. Rogers (2012) 206 Cal. App. 4th 669, 695–96.)

“Though mere opinions are generally not actionable [citation] a statement of opinion that implies a false assertion of fact is actionable.” (Issa v. Applegate (2019) 31 Cal. App. 5th 689, 702; Ruiz v. Harbor View Community Assn. (2005) 134 Cal.App.4th 1456, 1471 [“An opinion ... is actionable only ‘ “if it could reasonably be understood as declaring or implying actual facts capable of being proved true or false” ’ ”].)Further, “it is not the literal truth or falsity of each word or detail used in a statement which determines whether or not it is defamatory; rather, the determinative question is whether the ‘gist or sting’ of the statement is true or false, benign or defamatory, in substance.” (Issa, supra, 31 Cal. App. 5th at 702; Summit Bank, supra,206 Cal. App. 4th at 696 [“where an expression of opinion implies a false assertion of fact, the opinion can constitute actionable defamation”].)

In determining whether a statement declares or implies a provably false assertion of fact, courts apply the totality of the circumstances test. (Overhill Farms, Inc. v. Lopez (2010) 190 Cal. App. 4th 1248, 1261.) “Under the totality of the circumstances test, ‘[f]irst, the language of the statement is examined. For words to be defamatory, they must be understood in a defamatory sense.... [¶] Next, the context in which the statement was made must be considered.’ ” (Id. [citing (Franklin, 116 Cal.App.4th at 385.) “The ‘pertinent question’ is whether a ‘reasonable fact finder’ could conclude that the statements ‘as a whole, or any of its parts, directly made or sufficiently implied a false assertion of defamatory fact that tended to injure’ plaintiff's reputation.” (James v. San Jose Mercury News, Inc. (1993) 17 Cal.App.4th 1, 13.) “Whether challenged statements convey the requisite factual imputation is ordinarily a question of law for the court.” (Issa, supra, 31 Cal. App. 5th at703.)

The claims giving rise to the alleged defamation in the FAC are numerous—indeed, hard to keep track of. The FAC incorporates by reference all prior allegations, while also weaving separate “claims” into single paragraphs or lines. It “employs the disfavored shotgun (or ‘chain letter’) style of pleading, wherein each claim for relief incorporates by reference all preceding paragraphs, which often masks the true causes of action.” (International Billing Services, Inc. v. Emigh (2000) 84 Cal.App.4th 1175, 1179.) Making matters more difficult, the parties routinely refer to the defamatory statements in the abstract or general sense. The Court reminds the parties that under Baral, each separate defamatory “claim” subject to a special motion to strike must be treated as just that—separately. (See Baral, supra, 1 Cal.5th at 381-382.) This necessarily requires that the court and the parties analyze the text of each claim individually in their proper context.

Be that as it may, identifiable allegations include that Plaintiff was a “bigot,” “racist,” “abusive,” “pro-rape,” and “promoted hate speech,” among others. Plaintiff argues that considered in context, these defamatory accusations are not mere opinions and are false. The court addresses the specific claims that follow.

Violence Against Jehovah’s Witnesses:

On the Standleague website, Defendants published an article titled: “Are Leah Remini and A&E responsible for the Wave of Violence Against the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Kingdom Halls?” (FAC ¶ 119.) This arose from an “episode of The Aftermath” where Plaintiff allegedly attacked Jehovah’s Witnesses, provoking a wave of violence against Jehovah’s Witnesses Kingdom Halls in Washington in 2018.

Plaintiff contends there is no connection between her show and the violence against Jehovah’s Witnesses. She notes the show aired on November 13, 2018 (Remini Decl. ¶ 166), and that four of the five arson attacks happened before that date. (Farny Decl. Exh. 68.) But that misses the issue. It is difficult to conclude that the title of the article by itself implies a provably false assertion of fact. The title proposes the statement as a question. While the context within the article might prove helpful, Plaintiff fails to discuss or identify any defamatory statement actually contained in the article.

Considering this, Plaintiff has not met her burden on this claim. Therefore, this portion of paragraph 119 is ordered stricken.

Inspires Praise of Hitler:

Defendants published another article titled “As the World Remembers the Holocaust, Bigot Leah Remini Inspires Praise of Hitler.” (FAC ¶¶ 119, 273, 283; Farny Decl., Ex. 70) The story arose from a tweet by Plaintiff accusing the Church of “stalking” and “harassing” her. (Id.) A follower responded to that Tweet with the following reply: “In the 1940’s there was a certain European politician who had big ideas…. He had the right ideas, but went after the wrong groups…. Scientology is a plague and it needs to be exterminated.”(Farny Dec., Exhs. 70, 71.)

Again, an allegation in an article title that Plaintiff might have “inspire[d] praise of Hitler”—standing alone—is not a provably false assertion of fact.

Therefore, Plaintiff has not met her burden on this claim. Accordingly, the portions of paragraphs 119, 273,283 addressing this claim are ordered stricken.

Rape Apologist:

After Plaintiff testified for Paul Haggis at his rape trial, Defendants posted an open letter to the Game Show Network claiming the network employed a “rape apologist as their host.” (FAC ¶ 148.) Hate Monitor tweeted a photo of Plaintiff with a tattoo on her forehead reading: “I [heart] Rapists,” and wearing clothing supporting rapists. (Id. ¶ 126.) The text of the Tweets include the hashtag “#ReminiLovesRapists.” (Id.)

The doctored photographs here, while highly offensive and inappropriate, can only be deemed parody. A fact finder could not reasonably conclude the images make or imply a false assertion of defamatory fact.

Plaintiff goes on to argue the posts, asserted as fact, provide no factual bases for the statements. But the posts identified by Plaintiff in support of this argument (e.g., Singer Decl. Exhs. 11, 12) are not identified in the FAC. “As is true with summary judgment motions, the issues in an anti-SLAPP motion are framed by the pleadings.” (Med. Marijuana, Inc. v. ProjectCBD.com (2020) 46 Cal. App. 5th 869, 883.) “Because the issues to be determined in an anti-SLAPP motion are framed by the pleadings, we will not ‘insert into a pleading claims for relief based on allegations of activities that plaintiffs simply have not identified .... It is not our role to engage in what would amount to a redrafting of [a] complaint in order to read that document as alleging conduct that supports a claim that has not in fact been specifically alleged, and then assess whether the pleading that we have essentially drafted could survive the anti-SLAPP motion directed at it.’” (Id.) Therefore, these posts cannot form the basis of the claim.

Going further, Plaintiff has not produced evidence to conclude the posts identified in the FAC make or imply a false assertion of defamatory fact. Again, the posts are more appropriately considered parody. No reasonable person viewing them would consider them to mean that Plaintiff actually “loves rapists.” That Defendants provided no factual basis for saying Plaintiff loves rapists is exactly the point. No one viewing those statements could take them literally.

Therefore, Plaintiff has not met her burden on this claim. Accordingly, the portions of paragraphs 126, 148,273, and 283 are ordered stricken.

Abusive Employer:

Plaintiff contends that Defendants sent fake journalists to the set of “People Puzzler,” asking about “claims”that Plaintiff is allegedly abusive in the workplace. (FAC ¶ 152.) But the allegation does not appear to actuallyidentify any defamatory statement. That makes it impossible to analyze. Moreover, the motion is limited by the pleadings. (Med. Marijuana, Inc., supra, 46 Cal. App. 5th at 869.) Because an unidentified statement cannot be defamatory, the claim fails.

Therefore, paragraph 152 is ordered stricken to the extent it forms the basis of the defamation claims.

KKK, Neo-Nazi:

Defendants allegedly made a video comparing Plaintiff and the A&E network to Ku Klux Klan members.(FAC ¶ 115.) Also, in an open letter to the Game Show Network, Defendants expressed concern over plaintiff hosting on the network, and asked “What’s next? A game show ‘hosted’ by a KKK leader? Neo-Nazi Jeopardy?” (Id. ¶ 148.)

Plaintiff argues these statements, “when viewed in their specific factual context, are provably false.” (Opp. 17:15-16.) But again, Plaintiff fails to explain that factual context, or provide evidence to meet her prima facie burden that the statements are false.

Therefore, Plaintiff has not met her burden, and paragraphs 115 and 148 are ordered stricken.

Racism:

In videos using former Scientologists, Defendants allegedly made claims that Plaintiff was a racist. (FAC ¶90.) The Court of Appeal has explained that the term “racist,” while “exceptionally negative, insulting, and highly charged word,” is also “a word that lacks precise meaning, so its application to a particular situation or individual is problematic.” (Overhill Farms, Inc., supra, 190 Cal. App. 4th at 1262.) There is no bright-line rule as to whether claims of racism can form the basis of a defamation claim. Instead, like the defamation test more generally, the context in which the statements were made controls. (Id.)

As is now a pattern, Plaintiff only addresses the “racist” statements in sweeping terms. But she has not actually identified what was said that implicated she was a racist, nor the context of the same. She cannot meet her burden to establish a provably false statement of fact.

Accordingly, paragraph 90 is ordered stricken to the extent it alleges racism.

Statements by Plaintiff’s family that she is a liar and stole from them:

Defendants allegedly stated in videos that Plaintiff was abusive to her mother and daughter. (FAC ¶ 90.) In another video, Defendants “used and manipulated Ms. Remini’s estranged and now deceased father, George Remini and his third wife, Dana, to make false statements about Ms. Remini, including that she is a liar, that she only wanted her name in the news, that she would not help to pay for his cancer treatments, that she turned her back on her half-sister when she was in the hospital, that she ransacked her dying grandmother’s apartment, and that she has no morals.” (Id. ¶ 91.)

Plaintiff flatly denies that she ever abused her family members; that she turned her back on her father or her sister when they were ill; or that she “ransacked” her dying grandmother’s apartment. (Remini Decl. ¶¶ 33-35.) Plaintiff attests that she housed her father and paid for his treatments while he had cancer, paid her sister’s bills when she was in the hospital, and allowed her father to take what he wanted from her grandmother’s apartment. (Id. ¶ 33-34.) She also disputes the allegations of a poor relationship with her daughter. (Id. ¶ 77.)

First, the court would agree with Plaintiff that these claims are potentially provably false statements of fact. Through a fact-finding process, one could reasonably determine if Plaintiff had, in fact, been abusive to her mother and daughter, paid for her father’s cancer treatments, ransacked her dying grandmother’s apartment, or “turned her back” on the family.

A separate issue, raised by Defendants, is whether statements from Plaintiff’s family members, published by the Church on video, can give rise to defamation against the Church. Defendants argue they had no reason to know the statements were false, and had no obligation to “fact check” her family’s statements. (Reply 20: 19-20 [citing St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727 (1968)].) In St. Amant, the United States Supreme Court held in part that the failure to verify information does not demonstrate “actual malice” for purposes of defamation.(St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727 (1968).)

But St. Amant does not totally shield the Defendants here. “[E]ven in a public f gure case, a defendant's knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard can be proved by circumstantial evidence. Such factors as a failure to investigate the facts, or anger and hostility toward the plaintiff, may indicate that the defendant had serious doubts regarding the truth of the publication. The finder of fact must determine whether the publication was indeed made in good faith.” (Walker v. Kiousis (2001) 93 Cal. App. 4th 1432, 1446 [internal citations omitted].)

Here, Plaintiff provides enough evidence that Defendants made the publication with at least a reckless disregard of the facts. Defendants posted the videos at https://www.leahreminithefacts.org/videos/. (Emphasis added.) But Plaintiff insists Defendants knew these were not facts “because [she] told them” so. (Remini Decl.¶ 33.) Plaintiff attests she “communicated to Scientology how difficult [her] relationship was with [her] father and that [she] continually wanted to reestablish a relationship with him and provide support to him,” and that Scientology has documentation in [her] personal and confidential files that reflect this.” (Id. ¶ 33.) When considered in context of the calculated attack against Plaintiff, this is a prima facie showing of clear and convincing evidence of a reckless disregard of the facts, or, knowledge of their falsity.

Accordingly, Plaintiff has met her burden to establish the potential validity of this claim under the “minimal merit” standard. [FN 5]

c. Actual Malice

Defendants also argue Plaintiff’s defamation claims fail because as a “public figure,” Plaintiff cannot establish actual malice. They contend “even if Plaintiff can prove some of Defendants’ factual assertions are false, she will never be able to surmount her burden given each one was based on a reliable source, such as a family member or former colleague.” (Mtn. 33: 17-19.)

As an initial issue, this court must determine if Plaintiff is a public figure. It concludes that she is. “If the person defamed is a public figure, she cannot recover unless she proves, by clear and convincing evidence that the libelous statement was made with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” (Jackson, supra, 10 Cal. App. 5th at 1260 [cleaned up].) “The rationale for such differential treatment is, first, that the public figure has greater access to the media and therefore greater opportunity to rebut defamatory statements, and second, that those who have become public figures have done so voluntarily and therefore ‘invite attention and comment.’ ” (Id.)

As discussed earlier in this ruling, Plaintiff is a public figure. She’s a “two-time Emmy-award winning producer, actress and New York Times best-selling author.” (FAC ¶ 21.) Plaintiff became known for her role on the popular television show “The King of Queens.” (Remini Decl. ¶ 29.) She was the “public face” of Scientology. (FAC ¶ 70.)

She eventually made an intentionally “public departure” from the Church. (Id. ¶ 24.) Since leaving, Plaintiff has gone on to produce media critical of Scientology, apparently to much fanfare and attention: her book was a New York Times bestseller, and her A&E documentary was “award winning.” (Id. ¶¶ 93, 97.) She now publicly advocates against Scientology, and appears on various television shows and podcasts to do so. (Id. ¶24.) At the very least, Plaintiff concedes that she “is a limited public figure for purposes of the public controversy about Scientology.” (Opp. 13: 19-20; Billauer v. Escobar-Eck (2023) 88 Cal. App. 5th 953 [a limited purpose public figure, for purposes of a defamation claim, is one who voluntarily injects himself or is drawn into a particular public controversy and thereby becomes a public figure for a limited range of issues].)

The next issue is whether Plaintiff has made a prima facie showing of “clear and convincing” evidence that Defendants’ statements were made with “knowledge that [they were] false or with reckless disregard of whether [they were] false or not.” (Balla v. Hall (2021) 59 Cal. App. 5th 652, 682.) As already discussed, Plaintiff has done so.

As a “Suppressive Person,” Plaintiff has detailed in her declaration the lengths Defendants have gone to harass and humiliate her. That the attacks have continued or even increased after Plaintiff fi led this lawsuit supports a finding of actual malice. (Rinder Decl. 42-49; Remini Decl. 124-129.)

Mike Rinder, a former Scientologist and past member of its “Sea Org,” provides a declaration to corroborate Defendants’ bad faith. (Rinder Decl. ¶ 1.) As a former Scientology official, Rinder states he is “well aware of the types of Scientology’s methods to quell the voices of those who leave, speak out against or attack Scientology.” (Id. ¶ 4.) These tactics “include the type of character assassination, stalking, and harassment that Leah Remini…[has] been subjected to for many years.” (Id.) Rinder details Scientology’s “Fair Game” policy toward “Suppressive Persons,” which seek “obliteration” of Scientology’s enemies. (Id. ¶¶ 7.) Defendants have not presented any evidence conclusively defeating these claims.

Therefore, this court concludes that under the “minimal merit” standard, and assuming the evidence proffered by the Plaintiff is true, the statements giving rise to the defamation claims were made with actual malice. It follows that no claims are stricken on this ground.

2.

Merit of Plaintiff’s IIED Claim (Third Cause of Action)

The court now turns to Plaintiff’s cause of action for intentional infliction of emotional distress. “A cause of action for intentional infliction of emotional distress exists when there is ‘(1) extreme and outrageous conduct by the defendant with the intention of causing, or reckless disregard of the probability of causing, emotional distress; (2) the plaintiff's suffering severe or extreme emotional distress; and (3) actual and proximate causation of the emotional distress by the defendant's outrageous conduct. A defendant's conduct is ‘outrageous’ when it is so ‘extreme as to exceed all bounds of that usually tolerated in a civilized community. And the defendant's conduct must be ‘intended to inflict injury or engaged in with the realization that injury will result.’” (Hughes v. Pair (2009) 46 Cal.4th 1035, 1050-51, quoting Potter v. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co.(1993) 6 Cal.4th 965, 1001) (internal citations omitted). “Liability for intentional infliction of emotional distress ‘ “does not extend to mere insults, indignities, threats, annoyances, petty oppressions, or other trivialities.” (Bock v. Hansen (2014) 225 Cal. App. 4th 215, 233.) Severe emotional distress means “‘emotional distress of such substantial quality or enduring quality that no reasonable [person] in civilized society should be expected to endure it.’” (Id.) Where, as here, the plaintiff is a public figure and the IIED is based on speech, she must prove actual malice. (Blatty v. New York Times Company (1986) 42 Cal.3d 1033,1042.)

The court notes first that part of the basis for Plaintiff’s IIED claim is presumably the Defendants’ “pre-litigation surveillance.” (See, e.g., FAC ¶¶ 94, 106, 110,17 139, 173, 236.) Because Defendants did not meet their burden on that conduct under prong one, it need not be addressed under prong two. The same is true for the causes of action addressed later.

Here, where Plaintiff’s allegations have not already failed for a reason discussed in the preceding sections, this court concludes Plaintiff has met her burden to establish extreme and outrageous conduct done with the intention of causing, or reckless disregard of the probability of causing, Plaintiff’s emotional distress.

Plaintiff and Mike Rinder detail the thorough, harsh, and unrelenting campaign against Plaintiff, under the auspice of “Fair Game.” Plaintiff’s evidence also demonstrates that this caused her extreme emotional distress. Plaintiff attests in her declaration:

This decade-long, coordinated harassment of me, as well as my friends, family, and business acquaintances, has caused me severe emotional distress, has made me fear for my physical safety and that of my family, and has caused me to lose business opportunities. It has made me hesitant to accept new work engagements that I am offered, because I am fearful that any potential employers, their employees, their family, and their friends may be unfairly targeted by Scientology by virtue of their association with me. (Remini Decl. ¶ 68.)

Plaintiff has “incurred substantial economic expenses to protect [her] and [her] family’s physical and emotional health and safety.” (Id. ¶ 81.) From her time in Scientology, she knows “they will stop at nothing to utterly destroy [her] life.” (Id. ¶ 130.)

Considering the evidence—once again, which the court must accept as true for purposes of the anti-SLAPP—Plaintiff has established the requisite minimal merit of her claim for IIED. (Baral, supra, 1 Cal.5th at 384-85.)

Merit of Harassment Claim (First Cause of Action)

The court now turns to Plaintiff’s First Cause of Action for harassment. The allegations underlying the harassment claim are that Defendants “sen[t] harassing correspondence to Plaintiff and to others, and creat[ed]a social media smear campaign against Plaintiff that includes false and malicious accusations made against Ms. Remini, and at times, her family.” (FAC ¶ 227; see also FAC ¶ 231(a)-(c) [alleging physical harassment and surveillance, social media posts, and business interference].)

First, Defendants argue the cause of action fails on its face “as there is no private right of action for monetary damages created by Code of Civil Procedure Section 527.6.” (Mtn. 34: 17-19; Code Civ. Proc. § 527.6[providing for injunctive relief].)

Section 527.6 “establishes a special procedure specifically designed to provide for expedited injunctive relief to persons who have suffered civil harassment.” (Thomas v. Quintero (2005) 126 Cal. App. 4th 635, 648.)Petitions brought pursuant to section 527.6 are subject to attack by a special motion to strike under section425.16. (Id. at 652.)

The court would agree that section 527.6 provides only for injunctive relief, not monetary damages. Plaintiff has failed to provide authority showing otherwise. Thus, to the extent that claim seeks monetary damages, it fails. Nonetheless, plaintiff also seeks “an order enjoining Defendants” from the harassing conduct. (FAC ¶232.) The court therefore construes this cause of action as a section 527.6 petition. (See Ameron Internat. Corp. v. Insurance Co. of State of Pennsylvania (2010) 50 Cal.4th 1370, 1386 [When characterizing a complaint, it is policy to “emphasiz[e] substance over form].)

Defendant goes on to argue even construed as a “petition,” the claim still fails because Plaintiff cannot establish that their conduct “served no legitimate purpose.” As defined in the statute, “Harassment” is “unlawful violence, a credible threat of violence, or a knowing and willful course of conduct directed at a specific person that seriously alarms, annoys, or harasses the person, and that serves no legitimate purpose. The course of conduct must be that which would cause a reasonable person to suffer substantial emotional distress, and must actually cause substantial emotional distress to the petitioner.” (CCP § 527.6(b)(3)[emphasis added].)

Allegations pertaining to stalking and surveillance are not relevant here because they were deemed unprotected or not challenged under prong one. Therefore, the focus again is Defendants’ online statements.

Here, considering Plaintiff’s evidence, Plaintiff has established a “course of conduct” that constitutes harassment. (§ 527.6(b)(1).) Thus, where the alleged defamatory conduct has not already been stricken on other grounds, Plaintiff has established the requisite merit of her claim for civil harassment. (§ 527.6(b)(1).)[FN 6]

Merit of Stalking Claim (Second Cause of Action)

Plaintiff’s stalking cause of action is largely based on non-protected surveillance. However, Plaintiff also alleges “stalking of Plaintiff by posting threatening information to various websites and via social media on a continuing basis.” (FAC ¶ 236.)

Stalking requires a plaintiff prove three elements. First, Plaintiff must prove “a pattern of conduct the intent of which was to follow, alarm, place under surveillance or harass the plaintiff.” (Civ. Code § 1708.7, subd. (a)(1).) Second, that as a result of that pattern of conduct, she either (a) “reasonably feared for [her] safety, or the safety of an immediate family member,” or (b) “suffered substantial emotional distress, and the pattern of conduct would cause a reasonable person to suffer substantial emotional distress.” (Id., subd. (a)(2).) Third, Plaintiff must prove Defendants “made a credible threat with either (i) the intent to place the plaintiff in reasonable fear for his or her safety, or the safety of an immediate family member, or (ii) reckless disregard for the safety of the plaintiff or that of an immediate family member. In addition, the plaintiff must have, on at least one occasion, clearly and definitively demanded that the defendant cease and abate his or her pattern of conduct and the defendant persisted in his or her pattern of conduct unless exigent circumstances make the plaintiff’s communication of the demand impractical or unsafe.” (Id., subd. (a)(3).)

Defendants argue that Plaintiff cannot state an actionable stalking claim because their acts were constitutionally protected. (See § 1708.7, subd. (b)(1) [ “Constitutionally protected activity is not included within the meaning of ‘pattern of conduct.’”].) But “[i]n California, speech that constitutes ‘harassment’ within the meaning of section 527.6 is not constitutionally protected.” (Huntingdon Life Scis., Inc. v. Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty USA, Inc. (2005) 129 Cal. App. 4th 1228, 1250.) As discussed, Plaintiff has presented sufficient evidence showing a “pattern of” harassing conduct. (Civ. Code § 1708.7, subd. (a)(1).)

It is not difficult to imagine a credible threat based on the alleged surveillance. Those allegations are not subject to attack in this prong. But again, the allegations subject to the motion to strike are the posts on social media and websites. Plaintiff refers to threats in her declaration, but the content of these threats are not clear. Plaintiff has therefore failed to actually identify any “credible threat” occurring in these posts.

Accordingly, paragraph 236 of the Complaint is ordered stricken to the extent it alleges stalking based on the “posting [of] threatening information to various websites and via social media on a continuing basis.”

Merit of Tortious Interference with Contractual Relationship Claim (Fourth Cause of Action)

Plaintiff alleges Defendants’ interfered with her contracts with iHeartMedia and AudioBoom by sending disparaging communications to each. (FAC ¶¶ 247, 248.) These are the only two contracts expressly alleged in the cause of action. (See Med. Marijuana, Inc., supra, 46 Cal. App. 5th at 883 [“the issues in an anti-SLAPP motion are framed by the pleadings”].)

“The elements which a plaintiff must plead to state the cause of action for intentional interference with contractual relations are (1) a valid contract between plaintiff and a third party; (2) defendant's knowledge of this contract; (3) defendant's intentional acts designed to induce a breach or disruption of the contractual relationship; (4) actual breach or disruption of the contractual relationship; and (5) resulting damage.” (Pac.Gas & Elec. Co. v. Bear Stearns & Co. (1990) 50 Cal. 3d 1118, 1126.)

iHeartMedia:

On April 13, 2018, Plaintiff entered into a binding contract and profit-sharing arrangement with iHeartMedia +Entertainment, Inc., to produce a podcast on iHeartRadio. (Remini Decl. ¶ 83.) The parties amended the contract on May 1, 2020, to include two podcasts. (Id. ¶ 84.)

Plaintiff went on to co-host with Mike Rinder the Scientology: Fair Game podcast, detailing their time as Scientologists. (Id. ¶ 86.) On March 4, 2022, Defendants wrote and posted an article at https:/www.freedommag.org/ claiming that iHeartRadio “allows Remini, in obscenity-laced and abusive language, to insult, defame and demean Scientologists.” (Id. ¶ 87.) The article apparently details the Church’s attempts to interfere with the iHeartMedia contract. (Id. ¶ 88.) Plaintiff also cites “continuous efforts” by Defendants to end the contract, including sending agents to follow and harass podcast producers and staff. (Id.¶ 90.) Plaintiff asserts that iHeartMedia “grew so fearful” of the conduct that it decided to terminate the podcast. (Id.) iHeartMedia ended its contract with Plaintiff after the last episode aired on March 7, 2022. (Id. ¶91.)

To this evidence, Defendants respond that they are expressing an “opinion” and are “entitled to exercise their free speech rights to demand a broadcaster remove offensive content…” (Mtn. 37: 17-21.) Generally, the court agrees conduct of this type is not actionable.

But what the Church cannot do is send agents to harass the podcast’s producers and staff, to the point that they feared for their safety. (Remini Decl. ¶¶ 90-91.) Defendants fail to produce conclusive evidence to refute this. (See Baral, supra, 1 Cal.5th at 384-85 [court accepts plaintiff’s evidence as true].)

Therefore, Plaintiff has established the requisite minimal merit of her claim for tortious interference as it pertains to the iHeartMedia contract.

AudioBoom:

On August 1, 2022, Plaintiff contracted with AudioBoom Limited to be the exclusive audio advertising sales representative for the Scientology: Fair Game podcast for one year. (Remini Decl. ¶ 92.) On August 3, 2022,STAND sent a letter to AudioBoom CEO Stuart Last informing him that “AudioBoom will soon be syndicating the hate podcast of two rabid anti-Scientologists.” (Id. ¶ 93.) The letter goes on to explain that“[w]hen the podcast was last running, we reached out to companies to inform them this was the defamation and bigotry they were paying for through their advertising; we heard back from chief communications and marketing officers from Verizon to eBay confirming their ads were no longer running on this hate podcast. The podcast shortly thereafter lost all commercial advertising. Audioboom advertisers deserve the decency of being informed you intend to identify their brands with defamation and hate. We will be so informing them.” (Id.)

On August 10, 2022, STAND sent a letter to Julie Hansen, the US CEO of one of Audioboom’s advertisers, Babbel, addressing the podcast and stating, “[w]e trust that, like Verizon, eBay, State Farm and countless other companies, this kind of dehumanizing, hateful content violates your ad-buying guidelines and could not be further from your brand values. Audioboom syndicates hate. Please pull your advertising from this platform.”(Id. ¶ 94.)

On August 18, 2022, the Chief Content Officer of AudioBoom, Brendan Regan, emailed Plaintiff’s agents and informed them that STAND had been contacting AudioBoom’s advertisers to accuse AudioBoom of “promoting hate.” (Id. ¶ 95.) On August 22, 2022, STAND sent a letter to Candy Capital, a “significant investor” in Audioboom, asking it to “do something about [the podcast’s] syndication of hate.” (Id. ¶ 96.)